Turkey, you remember it was a complete economic write off only as recently as eight or nine years ago? In many respects its capital markets were so shambolic as to resemble another former economic basket case turned global investor darling... Indonesia

Your author remembers covering Indonesia as a terrorism analyst for a security company about seven-eight years ago and the only foreigners he seemed to encounter back in 2004-06 were security and terrorism analysts and wary mining/oil executives. These days you can't avoid stumbling over supermarket and other consumer goods execs, PE analysts and other financial types.

Think about that for a second: in eight years the country went from the domain of folks like Sidney Jones of the International Crisis Group to the stomping ground of Carlyle analysts. Sentiment CAN and DOES change. This is the same story for Turkey.... what does this mean for Club Med one wonders?

Think about that for a second: in eight years the country went from the domain of folks like Sidney Jones of the International Crisis Group to the stomping ground of Carlyle analysts. Sentiment CAN and DOES change. This is the same story for Turkey.... what does this mean for Club Med one wonders?

BACKGROUND

During the 1980s and 90s, Turkey had 15 governments, 10 of which were coalitions or minority governments. Unsurprisingly, getting anyone to make a serious and/or difficult choice on trivial matters of macroeconomic policy was nigh on impossible. Consequently, the country was plagued by chronic budget deficits, which in turn needed to be financed partially by printing money and thus stoked inflation of oh… around 30–50% during the 80s.

Under IMF-tutelage Turkey began in the mid-80s though to cut tariffs on imports, privatize SOEs, and reduce its social service expenditures. It also targeted attracting FDI through welcoming multinationals. This all seemed to be working well until the mid 90s when the country ran into recession due to budget deficits, political instability and resulting FDI and foreign portfolio outflows. This resulted in higher rates for government debt and a recession.

Inflation once again spiked (to a cool 120% or so at one point), and then in 1999 a 7.6 magnitude earthquake also hit the most populous and economically productive region of the country (the seven cities hit by the quake accounted for 34.7% of Turkey's GNP in 1998).

To sum it up: shit was in a bad way by the end of the 90s.

Inflation once again spiked (to a cool 120% or so at one point), and then in 1999 a 7.6 magnitude earthquake also hit the most populous and economically productive region of the country (the seven cities hit by the quake accounted for 34.7% of Turkey's GNP in 1998).

To sum it up: shit was in a bad way by the end of the 90s.

IMF STABILIZATION PROGRAM & THE CRAWLING PEG

1999's quake created the will to make a serious attempt to address the past decade's economic mess. The coalition government assembled a three-year time-frame, IMF-backed program in December 1999/January 2000 that called for a number of structural reforms (pensions, agricultural subsidies, SOE privatizations etc.) to put the budget on a sound footing, reduce the deficit and combat inflation which the IMF/government wanted to take down to 25% by 2000, 12% by 2001 and single digits by 2002. The public sector debt to GNP ratio was targeted at 54.8% by 2002 and a public sector primary surplus of 6.5% of GNP was also targeted for that year.

At its heart the IMF/Turkish government stabilization program though was an exchange rate-based effort supplemented by fiscal adjustments and structural reforms. So as to convince markets the lira would no longer be inflated away to fund deficit spending, it was to be tethered via a crawling peg against a US dollar-Euro/German mark basket. This would allow for interest rates to come down quickly, which was seen as essential to facilitate fiscal adjustment and support growth.

The crawling peg allowed the exchange rate to fluctuate within a pre-announced and staggered move through continuously widening bands to a free float within 18 months (July 2001). I.e. the peg had a built-in exit strategy with a deadline publicly announced at the very beginning to minimize the potential for speculative attacks (the Turks got a nasty lesson in how well that did not work about 14 months later).

The peg was to be backed by a firm money supply policy to bolster its credibility: the Central Bank of Turkey (CBT) would provide liquidity only in line with increases in its FX reserves. In effect, the CBT became a quasi-currency board and was unable to consider the daily requirements of the financial system as a priority. The peg also had another unusual feature: the CBT was not allowed to sterilise capital inflows.

At its heart the IMF/Turkish government stabilization program though was an exchange rate-based effort supplemented by fiscal adjustments and structural reforms. So as to convince markets the lira would no longer be inflated away to fund deficit spending, it was to be tethered via a crawling peg against a US dollar-Euro/German mark basket. This would allow for interest rates to come down quickly, which was seen as essential to facilitate fiscal adjustment and support growth.

The crawling peg allowed the exchange rate to fluctuate within a pre-announced and staggered move through continuously widening bands to a free float within 18 months (July 2001). I.e. the peg had a built-in exit strategy with a deadline publicly announced at the very beginning to minimize the potential for speculative attacks (the Turks got a nasty lesson in how well that did not work about 14 months later).

The peg was to be backed by a firm money supply policy to bolster its credibility: the Central Bank of Turkey (CBT) would provide liquidity only in line with increases in its FX reserves. In effect, the CBT became a quasi-currency board and was unable to consider the daily requirements of the financial system as a priority. The peg also had another unusual feature: the CBT was not allowed to sterilise capital inflows.

EARLY IMPACT OF THE PROGRAM

Initially, this worked well: inflation dropped from around 70% to a more modest (relatively speaking) mid-30s print within 8 months. Interest rates though fell even faster (i.e. negative real rates); growth took off, exceeding expectations, and the economy was pulled out of recession lifted by consumption and investment.

Interest rates and the yield curve were pushed down lowering the burden on interest payments and creating the illusion of lower default risk. This prompted further capital inflows and a feedback loop kicked in with the yield curve shifting further down. (Investors also noted a compelling arbitrage opportunity courtesy of the peg: the peg's pre-announced path theoretically eliminated FX risk and fiscal and structural reform measures theoretically cut default risk. The expected return from market interest rates now exceeded the risk-free return and the default risk. And hence the capital inflow took place.)

Unsurprisingly, the non-sterilisation rule meant the domestic economy was awash with liquidity: the monetary base expanded by 46% between February and mid-November.

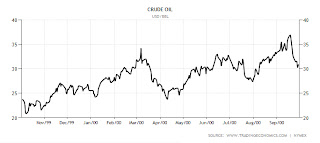

Meanwhile the USD was looking increasingly overvalued and oil prices were surging (although looking back at 1999/2000 $35/barrel seems pretty cheap!)

Interest rates and the yield curve were pushed down lowering the burden on interest payments and creating the illusion of lower default risk. This prompted further capital inflows and a feedback loop kicked in with the yield curve shifting further down. (Investors also noted a compelling arbitrage opportunity courtesy of the peg: the peg's pre-announced path theoretically eliminated FX risk and fiscal and structural reform measures theoretically cut default risk. The expected return from market interest rates now exceeded the risk-free return and the default risk. And hence the capital inflow took place.)

Unsurprisingly, the non-sterilisation rule meant the domestic economy was awash with liquidity: the monetary base expanded by 46% between February and mid-November.

Meanwhile the USD was looking increasingly overvalued and oil prices were surging (although looking back at 1999/2000 $35/barrel seems pretty cheap!)

Within a year the current account went from being in balance (on average) in 1999 to a deficit of about 5% of GNP owing to a huge surge in Turkish import demand thanks to a combination of higher oil prices and the more stable lira fueling a consumption boom underpinned by the strong dollar and rapid credit expansion/liquidity. Imports rose by 37% in the first eleven months of 2000, and the trade deficit more than doubled to $25 billion.

One thing the peg didn't do surprisingly though was aggravate a decline in exports. Most of the deterioration in the trade deficit was due to a boom in imports of goods and services rather than a decline in exports. In order to bankroll its import demands the country required capital inflows.

Admittedly, there was demand for this - the structural reform efforts meant ambitious privatisation programs, thus international capital initially flowed in. However, ideological differences within the ruling coalition led to a temporary stalemate in the pace of privatizations, especially with regard to a 33.5% sale of TurkTelekom and a 51% stake in Turkish Airlines, where military interests were also involved.

The inability to offload the TurkTelekom stake accounted for about half of the $4 billion shortfall in 2000 privatization receipts alone (the government was aiming to raise $7.5bn in privatization revenue that year), while complications in the contracting process for energy privatizations delayed the inflow of FDI into that sector and a failure to pass state banking privatisation legislation, in turn, delayed the approval of a $780 million World Bank loan. The country was being primed for a classic balance of payments headache.

The resulting delays affected both fiscal policy and the capital inflows necessary to finance the growing current account deficit, meanwhile initial international investor optimism began to flag and a net capital inflow of US$ 11.1 billion in the first nine months of 2000, turned to an outflow in September resulting in a (very small) decline in the net international reserves of the central bank that month.

Moreover,the local banks (particularly private ones) were also aggressively out in the international market financing themselves with short term foreign money to lend in lira to capture the spread and FX gains.

With rates moving up more markedly in November levered banks with already thin capital cushions were forced to offload their treasury holdings at a loss to maintain liquidity in the face of increasing funding costs on the wholesale market and the default risk on Turkish treasuries was rising. It probably didn't help that in October and early November the banking regulator acted on rumours of malpractice and two banks - Etibank and Bank Kapital - were brought under management of the Savings Deposit Insurance Fund (SDIF). Rumors then began doing the rounds about illiquid mid-tier banks and their FX exposure.

The poster-child for this insanity was the mid-sized Demirbank (which also happened to be a partner bank to the recently seized Etibank): the ratio of its government debt portfolio-to-total assets was about twice the size of other private banks. Demirbank had ceased to become a traditional gatherer of deposits to lend and had morphed into a huge hedge fund with one punt: bet big on lower rates.

Depending on who you read, before the November 2000 liquidity implosion the bank held between 15-18% of outstanding Turkish bonds, this was approximately $7.5bn on paid-in capital of $300mn (this was also possible as the banking rules allowed govt debt to be considered risk free in the asset weighting rules). If that kind of leverage and concentration risk strikes you as nuts the bright sparks at Demirbank were also funding about 70% of their bond portfolio through repos…

In theory, the Central Bank of Turkey (CBT) should have stepped in to provide lira liquidity as banks rushed to dump their Turkish treasuries and swap them into dollars with the CBT. However, given the peg and a belief it was key to the government's anti-inflation commitment the CBT as a de facto currency board was not only unable to set interest rates but also felt going into November 2000 it could not act as lender of last resort to commercial banks by providing liquidity in the interbank market by releasing lira reserves.

Politicians were also hoping that given the peg-driven boom they could maintain the system with help from IMF funding to the CBT rather than trigger a devaluation that would result in a collapse in domestic demand and inflation.

So the fire sale began, Demirbank began dumping more bonds into an illiquid market at ever lower prices, which further drove up rates stoking more capital outflows and draining ever more lira liquidity and foreign reserves out of the system. That short Turkish rates trade the banks had on was looking less tasty.

By November 22 full-scale panic broke out (Black Wednesday). When it became apparent how messy things were getting CBT policy reversal kicked in and it began providing funding to the market by purchasing government securities and lending to banks in need of short-term funding on the inter-bank market.

However, the amount of liquidity it injected in promptly made its way back to the CBT in the form of demand for dollars. Everyone was taking advantage of the liquidity to move as fast as they could for the exit.

The stock market tanked 30% in a week and a half (yes, you read that correctly about a third of the index's capitalisation vaporised in eight trading days) and govvies went from a 40 to 85% yield...

Admittedly, there was demand for this - the structural reform efforts meant ambitious privatisation programs, thus international capital initially flowed in. However, ideological differences within the ruling coalition led to a temporary stalemate in the pace of privatizations, especially with regard to a 33.5% sale of TurkTelekom and a 51% stake in Turkish Airlines, where military interests were also involved.

The inability to offload the TurkTelekom stake accounted for about half of the $4 billion shortfall in 2000 privatization receipts alone (the government was aiming to raise $7.5bn in privatization revenue that year), while complications in the contracting process for energy privatizations delayed the inflow of FDI into that sector and a failure to pass state banking privatisation legislation, in turn, delayed the approval of a $780 million World Bank loan. The country was being primed for a classic balance of payments headache.

The resulting delays affected both fiscal policy and the capital inflows necessary to finance the growing current account deficit, meanwhile initial international investor optimism began to flag and a net capital inflow of US$ 11.1 billion in the first nine months of 2000, turned to an outflow in September resulting in a (very small) decline in the net international reserves of the central bank that month.

Moreover,the local banks (particularly private ones) were also aggressively out in the international market financing themselves with short term foreign money to lend in lira to capture the spread and FX gains.

BANKING SYSTEM (OR LACK OF A SYSTEM)

Yeah, so you think we potentially have the recipe for a disaster here?

Well, it didn't help that state banks were not required to provide reserves for bad loans, and were not subject to serious supervision. Why was this?

State banks had been ‘allocated’ to different political parties and interest groups to provide subsidized credits to their constituencies (primarily agricultural support in the wake of structural reforms in the 1990s).

Previously these funds (i.e. before 1994's economic crisis) would be directly paid by the government out of the government budget but because of attempts to reign in the deficit, politicians attempted to short-circuit this by getting state banks to make 'loans' instead to the prior recipients of these payouts.

These 'loans' to the Turkish Treasury appeared as illiquid assets on the banks balance sheets, however, these loans did not appear as liabilities on the treasury's balance sheet. Thus, making them a huge form of off-balance sheet financing for the government… who had an ambiguous commitment to pay back at some point some time, somehow, somewhere to the banks.

These bank 'assets' (otherwise known as 'duty losses') exploded to about 13% of GNP by 1999 from 2.2% of GNP in 1995 (or from $2.77bn to $19.2bn), according to the World Bank. To put this further into perspective the state banks had about $22bn in short-term liabilities and FX exposure of $18 billion. Their balance sheets were well and truly illiquid/insolvent if anyone came along and pushed them.

The circus didn't stop with the state banks. Weak rules on asset valuation allowed banks to overstate their financial positions and rules on connected lending were lax/non-existent. Thus, in a similar set-up to the Japanese zaibatsu, private banks were generally affiliated with a family of businesses and the controlling shareholder would use the bank as their de facto conglomerate treasury.

By late 2000 local media had run numerous stories of corruption and malpractice in several private banks and eight banks had failed and been taken over by the Savings Deposit Insurance Fund (SDIF) by late 1999. These continued to operate without corrective actions despite growing losses and distortions. As depositors and bank creditors were fully protected under a blanket state guarantee in effect since 1994 there were no bank runs.

By late 2000 local media had run numerous stories of corruption and malpractice in several private banks and eight banks had failed and been taken over by the Savings Deposit Insurance Fund (SDIF) by late 1999. These continued to operate without corrective actions despite growing losses and distortions. As depositors and bank creditors were fully protected under a blanket state guarantee in effect since 1994 there were no bank runs.

Can you say "Moral Hazard"?

The mid-sized private banks, in particular, were also out in the international wholesale market funding themselves at the short-end to position themselves aggressively for continuing declines in interest rates (not completely unreasonable given the backdrop). With these short-term overseas FX-denominated funds they were ramping up their exposure to long-dated Turkish treasuries and making plenty of fixed rate consumer credits. (You can see where this is heading... maturity mismatch.)

The mid-sized private banks, in particular, were also out in the international wholesale market funding themselves at the short-end to position themselves aggressively for continuing declines in interest rates (not completely unreasonable given the backdrop). With these short-term overseas FX-denominated funds they were ramping up their exposure to long-dated Turkish treasuries and making plenty of fixed rate consumer credits. (You can see where this is heading... maturity mismatch.)

LIQUIDITY CRISIS

The widening current account deficit and delays to the privatisation program had been causing interest rates to rise from September 2000. However, the government ignored IMF advice to rein in demand, which added to concerns about the banking system - in fact, in a complete policy reversal the IMF told Turkish policy makers in September 2000 to consider dropping the peg to halt the outflow of Central Bank reserves to allow it to bring down the interest rate to avoid a massive debt default and pick up the pieces of economic policy from there.

With rates moving up more markedly in November levered banks with already thin capital cushions were forced to offload their treasury holdings at a loss to maintain liquidity in the face of increasing funding costs on the wholesale market and the default risk on Turkish treasuries was rising. It probably didn't help that in October and early November the banking regulator acted on rumours of malpractice and two banks - Etibank and Bank Kapital - were brought under management of the Savings Deposit Insurance Fund (SDIF). Rumors then began doing the rounds about illiquid mid-tier banks and their FX exposure.

The poster-child for this insanity was the mid-sized Demirbank (which also happened to be a partner bank to the recently seized Etibank): the ratio of its government debt portfolio-to-total assets was about twice the size of other private banks. Demirbank had ceased to become a traditional gatherer of deposits to lend and had morphed into a huge hedge fund with one punt: bet big on lower rates.

Depending on who you read, before the November 2000 liquidity implosion the bank held between 15-18% of outstanding Turkish bonds, this was approximately $7.5bn on paid-in capital of $300mn (this was also possible as the banking rules allowed govt debt to be considered risk free in the asset weighting rules). If that kind of leverage and concentration risk strikes you as nuts the bright sparks at Demirbank were also funding about 70% of their bond portfolio through repos…

When delays hit a Demirbank foreign-loan syndication, the bank suddenly found its wholesale/interbank market lines of credit cut and foreign lenders simply exited the overnight market resulting in zero liquidity. Demirbank was forced to dump its Turkish treasury bills at a loss to meet margin calls.

Politicians were also hoping that given the peg-driven boom they could maintain the system with help from IMF funding to the CBT rather than trigger a devaluation that would result in a collapse in domestic demand and inflation.

So the fire sale began, Demirbank began dumping more bonds into an illiquid market at ever lower prices, which further drove up rates stoking more capital outflows and draining ever more lira liquidity and foreign reserves out of the system. That short Turkish rates trade the banks had on was looking less tasty.

By November 22 full-scale panic broke out (Black Wednesday). When it became apparent how messy things were getting CBT policy reversal kicked in and it began providing funding to the market by purchasing government securities and lending to banks in need of short-term funding on the inter-bank market.

However, the amount of liquidity it injected in promptly made its way back to the CBT in the form of demand for dollars. Everyone was taking advantage of the liquidity to move as fast as they could for the exit.

The stock market tanked 30% in a week and a half (yes, you read that correctly about a third of the index's capitalisation vaporised in eight trading days) and govvies went from a 40 to 85% yield...

Accelerating capital outflow driven by fears that the financial and exchange rate system were about to collapse caused overnight rates to climb above 1000%. Then suddenly the CBT once again changed tack. On November 30 to stem the reserves outflow, it announced it would no longer fund commercial banks in the inter-bank market and it would return to its net domestic asset upper limit, which was to be reset as of 1 December at its 30 November value. This announcement pushed the overnight rates to 1,700% on December 1.

IMF BAILOUT DECEMBER 2000

The peg had been put under huge pressure; between November 20- December 5 alone a $6.4 billion net foreign exchange outflow occurred (around 1/4 of the total reserves of the CBT). The wise thing to have done would have been to jettison the peg but too much political capital had been invested in the system by both the IMF and government only 12 months earlier.

On December 6, Demirbank was taken over by the SDIF and the IMF stepped in with a total $10 billion package to bolster the CBT FX reserves and support the peg in return for a tightening of the stabilization program, which included strengthening the primary surplus target for 2001 from 3.75% to 5%!?

The following week, the Treasury secured a $1 billion syndicated loan from international banks meeting in London, to signal their support for the program and by the end of December, overnight interest rates had fallen to under 100% signalling an uneasy calm. Central Bank reserves also rose from $18.3 billion on 5 December to $28.2 billion by 15 February.

However, the IMF funds could only be used against a speculative attack on the currency and did not provide a solution to the initial problem of a liquidity crunch (i.e. as the peg was still in place the CBT remained a currency board and thus was unable to act as a lender of last resort).

As a result, the decline in the interest rates was not rapid, high interest rates prevailed in the first months of 2001 (even though rates came down post-IMF bailout they were still four times higher than levels that prevailed at the beginning of November), eroding further the equity of the commercial banks until the second crisis, which erupted on February 2001.

PEG COLLAPSE FEBRUARY 2001

Relations between President Ahmet Necdet Sezer and Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit had been deteriorating over 2000 due to Sezer's constant vetoing of government decisions. On February 19 at a National Security Council meeting Sezer accused the government of dragging its feet in the fight against corruption and on investigations of banks. Prime Minister Ecevit stormed out of the meeting, called a press conference and told the media there was ‘a crisis at the very top of the state.’ Unsurprisingly, given the political turmoil that had existed during the 80s and 90s this totally spooked the markets, which were still trying to get over the liquidity crunch of November.

Overnight rates spiked from from 43.7% on 19 February to 2,057.7% on 20 and 4,018.6% on 21st causing $2.5 billion in losses for the two largest state banks, or about 2% of GNP. The ISE-100 index collapsed 14% on the 19th and over the next few days the market continued to nose-dive. There was a huge surge in demand for dollars, the CBT was forced to spend more than $7.6 billion, which exceeded 1/5 of its currency reserves, in order to maintain the exchange rate.

By February 22 the authorities conceded defeat and the lira was allowed to float, depreciating immediately by some 40% to 958,000 against the USD and the ISE-100 tanked 18% that day.

That day Moody’s also lowered Turkish rating position for debt denominated in foreign currency and bank deposits from positive to stable(!?). Fitch decreased the long-term rating for debt denominated in local/ national currency from BB to B+ and put all the ratings of the country under observation in negative perspective. (Ratings agencies ever ahead of the curve, eh?)

The ISE-100 rallied 10% on February 23rd and the inter-bank interest rate also decreased from 5000% to… between 1000-2000%! (Still enough to kill most of the banking system). Banks immediately began to default in the market for short-term funds, and this triggered a severe recession.

By April the lira had lost 70% of its value against the dollar and sparked a significant rise in inflation, a fall in population’s purchasing power, rapid shrinkage of consumption and substantial losses for SMEs.

Despite a sharp turnaround in the current-account balance brought about by the collapse in economic activity and the freeing of the central bank from its obligation to defend the currency peg, reserves fell drastically as a result of capital flight – some $6 billion between the date of the float and end September 2001. For the whole period from the outbreak of the November crisis, net capital flows amounted to some $17 billion, primarily driven by non-residents which had to be fully covered from reserves (including borrowing from the IMF), since the current account was also in deficit during that period.

MACRO RESTRUCTURING

In May 2001 Turkey went to the IMF to signal responsibility and guarantee the implementation of the new economic program and in general terms reaffirm projected macroeconomic indicators for GNP growth, the inflation rate and the current budget deficit. Later that month both the IMF and World Bank agreed to extend Turkey credits for $12.0 billion and $2.5 billion, respectively.

Monetary policy would move towards inflation targeting, with greater independence for the Central Bank. Renewed commitments were made to privatise state-owned economic enterprises (SEEs) and to foster greater FDI.

The IMF initially wanted to see a CPI target of 20% for end-2002 but negotiations between the IMF and Turkey resulted in a 35% target. (This was ultimately met)

Public sector wage caps were also renegotiated as it was felt that a general strike spearheaded by representatives of Turkish Airlines would be more damaging to the economy (particularly on the tourist sector) than the increase in wages that the unions were seeking.

A public sector primary surplus of 6.5% of GDP by 2002 was also targeted so as to remove concerns about debt sustainability and for maintaining full commitment to the program. However, the negative impact of the 9/11 attacks, the rise in expectations for elections within the political environment and the rising real interest rates and the failure of policies related to the income support caused deviations from the target.

Unsurprisingly, banks took huge hits to their balance sheets in 2000-2001 and there was a huge consolidation in the number of banks operating in the country between 2000-2002. Given the way the banking system had run itself a huge recap was necessary to sort out balance sheets. The total cost of this came in at around $47 billion – one-third of Turkey’s national income. Excessive leverage, maturity and currency mismatches were tackled and risk management improved.

A new economic minister, Kemal Dervis, was brought in to deal with the mess. Given the plunge in the lira the cost of servicing foreign debt had risen considerably for the government (although the flip side was the CBT no longer needed to waste its reserves on defending the peg). Dervis and his team considered a default but given over 60% of all government debt was held by domestic banks an involuntary restructuring would have severely damaged the domestic economy and retarded any recovery. Had the debt been externally held then a default would probably have been more likely.

STATE BANKS

Legislation was passed to deal with state banks, these were privatised over a number of years and turned from from state enterprises to corporations. They were also operationally restructured with links to line ministers cut and new independent professional boards appointed for Ziraat and Halk. In addition, the state banks became subject to all BRSA regulations applicable to private banks.

Duty loss receivables exceeded 50% of banks’ assets by the end of 2000 (50% in Ziraat Bankası and 65% in Halk Bankası). Duty losses which were $17.5 billion as of end 2001 were liquidated and these obligations were shifted onto the Treasury balance sheet in exchange for special issue treasuries, regulations leading to duty losses were also abolished. The fresh injection of capital made it possible for the state banks to fully eliminate their FX exposure and repay their overnight money market debt.

The depegging of the lira also allowed the CBT to provide liquidity to the banks through more traditional monetary policy instruments. Based on an aggressive valuation of the banks’ assets, the government injected an additional $2.9 billion in government securities to raise the capital adequacy ratios of the two large state banks, Ziraat and Halk, above the required minimum of 8 percent.

The recapitalization and downsizing under new management meant state banks immediately became profitable, which allowed them to pay hefty dividends to the Treasury. Ziraat accumulated so much surplus capital that it was able to pay the government a special dividend of $2 billion. Considering that, in early 2001, the value of these banks was close to zero, this was pretty successful.

PRIVATE BANKS

All undercapitalized banks were required to submit detailed and time-bound plans on how they would raise additional capital by end-2001.

Persistently high interest rates continued to cause concerns about portfolio losses at lenders and market rumors persisted about asset overvaluation implying some banks would not be able to raise more capital, if faced with additional losses. To tackle this a support scheme that would make public funds available to help banks that could not raise new capital on their own was drafted based on the scheme that had been used successfully in Thailand in 1998.

The public funds scheme was deliberately structured to incentivize shareholders to invest their own resources rather than to give the SDIF a role in managing banks. The conditions included:

(i) such support should be viewed as a last resort;

(ii) existing shareholders or new private investors had to match the public contribution;

(iii) there would be no bail-out of existing shareholders;

(iv) the bank had to have a positive net worth;

(v) the government had the right to appoint at least one board member; and

(vi) existing shareholders were required to pledge as collateral to the government shares held in the bank equal to the government’s contribution.

As it turned out no private bank needed capital assistance. One large bank, Pamuk, could not raise the $2 billion needed to enter the scheme and was taken over by the SDIF.

Indeed, banking failures/consolidation rapidly dropped off going into 2003. One embarrassing episode though was a relatively small family owned bank, Imar, became illiquid owing to massive deposit withdrawals in 2003. It was later discovered most accounting records had disappeared and deposit liabilities were ten times higher than officially reported due to an elaborate parallel banking operation. In order to maintain confidence though it was felt that depositors had to be paid in full, at an initial cost to SDIF of more than $6 billion. The happy ending to the story is that the SDIF was able to recover the full amount by confiscating and liquidating assets of the bank’s owning family.

Another telling indicator of restored confidence in banks has been a marked shift by depositors since 2002 from foreign currency back into lira deposits.

RECOVERY

The economy turned around remarkably quickly as the program restored confidence. Industrial production began rising in late 2001, and the first half of 2002 saw the recovery in output gathering strength, combined with a 30% point drop in inflation. Business confidence surged into positive territory, and – after a sharp drop in the wake of the September 11 events – the stock market took off.

From Q1 2002 to mid-2008, the Turkish economy grew by over 5% YoY, and inflation declined markedly. While global economic and financial conditions were favorable, it is hard to argue that the reforms mentioned above did not contribute positively toward achieving these growth rates.

No comments:

Post a Comment