Before the onset of the 1997-98 crisis, South Korea was, at least on the surface, doing fine economically. It was one of the world’s fastest growing economies with an average annual growth rate of 7-9% and modest inflation of about 5% a year for the three years leading up to the crisis. The ratio of its foreign debt to GDP was less than 30%, the lowest among developing countries and less than that of many industrially advanced countries. In addition, the government’s budget was balanced. However, in the end none of that mattered...

In January 1997 the Hanbo Group declared bankruptcy. Hanbo (primarily focused on steel) was the 14th largest chaebol and thus like the other chaebol that had blown up previously was a second division player. Other second & third tier names also started failing under their debt: Sammi Steel in March (no. 26 by assets) and Jinro Group in April (no. 19 by assets). By July (note this was the same time when Thailand devalued the baht) the rot though had spread well up the food chain. Kia, the eighth largest chaebol with a total of 28 affiliates, began to run into problems with an election underway in Korea a clear decision on a bailout or state aid to the conglomerate was delayed, which added to investor uncertainty.

The Kia Group's financial difficulties stemmed from its heavy debt burden and reduced ability to service its debt to deteriorating business conditions.

At the end of May 1997, the Kia group had a 14.1 trn won balance sheet, of which 2.3trn won was equity and it owed 9.5 trn won in debt, i.e. a cyclically positioned conglomerate was levered roughly 5:1. Its debts and losses were attributed primarily to three subs: Kia Steel, truck maker Asia Motors and Kisan (construction). The problems at these three eventually led to cash flow problems for the group as a whole, or rather its core business that was the only one that really generated any cashflow: the profitable Kia Motors.

Kia in theory should have shut down or jettisoned its subs, but Korean business culture did not permit this and a highly unionized workforce further complicated restructuring. (Unusually for a chaebol, employee unions were major shareholders at Kia making them reluctant to dump struggling subs and delaying a swift resolution to its default of $370mn of debt in July.)

What really put the entire group on the hook though were the cross debt guarantees issued by the core Kia Motors business. This allowed its loss-making affiliates to gain easier loan terms and thus finance the group's expansion. Kia Motors provided guarantees of about 2.24 trillion won, accounting for 88.4% of the group’s total guarantees that were valued at 2.54 trillion won. Due to the guarantees, Kia could not promptly restructure itself or cut off ailing affiliates and issues with its subs quickly engulfed the parent.

A further wrinkle to restructuring was that intragroup trading comprised a particularly high percentage of sales at Kia. Untangling its group companies to operate as stand alone entities was problematic/unviable.

CHAEBOL

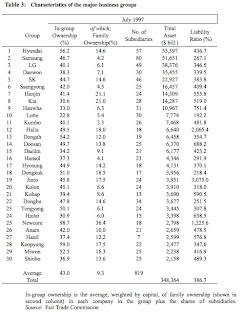

Korea's economy was dominated by a large number of conglomerates (Chaebol) that enjoyed privileged market access and economic powers. Their existence was encouraged by the state during the initial stages of Korean economic development in the 1960s and 70s as an engine for fast growth. Government policies favored Chaebol expansion via financial assistance: low interest rates, tax benefits, foreign exchange allocations, import and export licenses and foreign investment incentives etc.

This allowed the Chaebol to engage in aggressive capacity expansion via cheap debt financing, meanwhile byzantine corporate structures centralized control in the hands of founding families via minority stakes, allowing management to ignore minority shareholders. (There was a now defunct blog called Uprofish - bizarre name - that had an incredible diagram of the corporate structure of Hyundai a few years ago showing how very small stakes, circular ownership and cross-shareholdings allowed the Chung family to control a huge commercial empire.)

This allowed the Chaebol to engage in aggressive capacity expansion via cheap debt financing, meanwhile byzantine corporate structures centralized control in the hands of founding families via minority stakes, allowing management to ignore minority shareholders. (There was a now defunct blog called Uprofish - bizarre name - that had an incredible diagram of the corporate structure of Hyundai a few years ago showing how very small stakes, circular ownership and cross-shareholdings allowed the Chung family to control a huge commercial empire.)

The privileged position of Chaebols led to moral hazard among investors and owners that the government would not let them fail. In reality, this was flawed reasoning. Between 1990 and 1996 three of the 30 biggest chaebols went bankrupt: Hanyang, Yoowon, and Woosung, according to HJ Chang. (I was only able to find an internet reference to the bankruptcy of one of these conglomerates - Woosung the 28th biggest chaebol in 1996. Thus, by most measures this was a smallish conglomerate so one can still see how the TBTF mentality would have prevailed for many investors but the point is clear, don't take TBTF for granted.)

In January 1997 the Hanbo Group declared bankruptcy. Hanbo (primarily focused on steel) was the 14th largest chaebol and thus like the other chaebol that had blown up previously was a second division player. Other second & third tier names also started failing under their debt: Sammi Steel in March (no. 26 by assets) and Jinro Group in April (no. 19 by assets). By July (note this was the same time when Thailand devalued the baht) the rot though had spread well up the food chain. Kia, the eighth largest chaebol with a total of 28 affiliates, began to run into problems with an election underway in Korea a clear decision on a bailout or state aid to the conglomerate was delayed, which added to investor uncertainty.

The Kia Group's financial difficulties stemmed from its heavy debt burden and reduced ability to service its debt to deteriorating business conditions.

At the end of May 1997, the Kia group had a 14.1 trn won balance sheet, of which 2.3trn won was equity and it owed 9.5 trn won in debt, i.e. a cyclically positioned conglomerate was levered roughly 5:1. Its debts and losses were attributed primarily to three subs: Kia Steel, truck maker Asia Motors and Kisan (construction). The problems at these three eventually led to cash flow problems for the group as a whole, or rather its core business that was the only one that really generated any cashflow: the profitable Kia Motors.

Kia in theory should have shut down or jettisoned its subs, but Korean business culture did not permit this and a highly unionized workforce further complicated restructuring. (Unusually for a chaebol, employee unions were major shareholders at Kia making them reluctant to dump struggling subs and delaying a swift resolution to its default of $370mn of debt in July.)

What really put the entire group on the hook though were the cross debt guarantees issued by the core Kia Motors business. This allowed its loss-making affiliates to gain easier loan terms and thus finance the group's expansion. Kia Motors provided guarantees of about 2.24 trillion won, accounting for 88.4% of the group’s total guarantees that were valued at 2.54 trillion won. Due to the guarantees, Kia could not promptly restructure itself or cut off ailing affiliates and issues with its subs quickly engulfed the parent.

A further wrinkle to restructuring was that intragroup trading comprised a particularly high percentage of sales at Kia. Untangling its group companies to operate as stand alone entities was problematic/unviable.

Eventually, the government stepped in and put the group’s two auto units -- Kia Motor and its subsidiary Asia Motor -- under court receivership. Kia Motor was recapitalized with state funds, the state-run Korea Development Bank converted Kia’s debt into investment capital and Kia Motors and Asia Motors were ulitmately sold to Hyundai Motors Co. in November 1998.

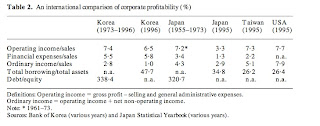

These problems of excessive leverage, over-expansion, cross-loan guarantees and poor (group-wide) profitability were not unique to Kia. The average debt-equity ratio for the Korean manufacturing sector reached nearly 400% in 1997, double the OECD average, and the average ratio for the top 30 chaebols exceeded 500%.

A negative terms-of-trade shock brought on by a rapid decline in prices for semi-conductors, steel and chemical products pressured already thin profit margins of chaebols and accelerated the downtrend of already structurally modest ROICs at these conglomerates going into 1995 (this also on a macro level aggravated Korea's current account deficit). Increasing wages at chaebol over the previous few years also did little to help.

A jump in the current account deficit in 1991 to $8.7bn pushed Seoul to encourage capital inflows to finance the deficit, this was done by amending the Foreign Exchange Management Act. As exports accounted for 40% of Korea’s GDP the regulatory focus on the liberalization was on the effect of capital inflows on the competitiveness of Korean exports through the appreciation of the Korean won rather than the feedthrough effect of capital inflows on financial system stability.

At end of 1996, Korea’s current account recorded a deficit of $23 billion, compared to a deficit of $8.5 billion at year-end 1995. This jump was brought on by the adoption of a strong-dollar policy adopted by the US in 1995 that caused Korean export competitiveness to suffer, particularly vis-a-vis the yen. A further headwind arose as the Chinese devalued the yuan.

In addition, FX reserves at end-1996 was equivalent to just 2.8 months of imports.

On the other hand, short-term borrowing was mainly regarded as trade-related financing requiring no strict regulation.

Quelle surprise, in 1998, 16 of the 24 (i.e. 2/3!!!??) merchant banks needed to be liquidated.

The government’s implicit guarantee to maintain the FX rate misled business into believing FX risk did not exist. Accordingly, businesses (primarily Chaebol) and merchant banks did not consider the potential increase in the domestic cost of foreign debt.

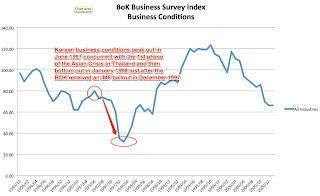

In July 1997, having exhausted its FX reserves, Thailand's decided to float the Thai Baht and crystalized the first round of the Asian Financial Crisis. It took a few months for contagion to move north. For example, in September the Korea Development Bank, a state-run bank, was still able to issue $1.5 billion in global bonds without any difficulty. (Indeed, not only was it the largest foreign currency bond issue ever offered by a Korean bank or corporation the bank upped its offering by $500mn to $1.5bn to meet foreign demand as Southeast Asian economies stumbled.)

However, by October the Won began to depreciate rapidly.

On October 24, two days after the government announced a rescue plan for Kia, Standard and Poor’s, a U.S. credit rating firm lowered its rating on Korea’s long-term foreign-currency sovereign debt to single A-plus from double A-minus. This was the first time the nation’s credit rating had been cut, although some of Korea’s corporations and banks had been downgraded. S&P explained its action citing “the escalating cost to the government of supporting the country’s ailing corporate and financial sectors.” The government rescue of Korea First Bank (KFB) in September made the government’s official backing of the banking system’s obligations increasingly explicit.

By November 10, the won/dollar rate passed the 1,000 mark for the first time, and on November 16 Michel Camdessus, Managing Director of the IMF, secretly visited Seoul to discuss rescue loans. On November 17, another effort to soothe foreign investors’ concerns failed when the National Assembly failed to approve a package of 13 financial reform bills before the end of the regular session.

On November 19, the government announced a raft of financial stabilization measures intended to encourage stem the flow of portfolio funds out of the Korean economy. These measures included:

However, a rapid infusion of hard currency reserves was critical to stabilize confidence and of the $58.4 billion, $23.4 billion was reserved as a second line of defense that would be made available to Korea by G-7 countries only if the initial amount of $35 billion contributed by the IMF and other multilateral institutions proved inadequate.

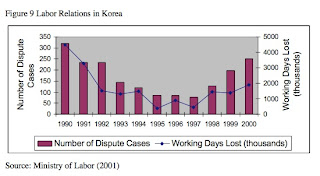

Labor regulations relating to layoffs were introduced in February 1998 in the face of strong union resistance but at the insistence of the IMF. The new layoff law allowed companies to dismiss workers without union consent when the firm faced “emergency situations” such as an M&A. Other legislation covered bankruptcy, corporate liquidation and employment insurance, all aimed at speeding up the reform of industry structure and financial markets. Hostile mergers and acquisitions of domestic firms by foreigners were allowed as the Assembly approved a bill on the introduction of foreign capital.

Hyundai Motors announced plans for to layoff about 20 percent of its 45,000 work force in order to overcome sluggish sales and overcapacity in May 1998. This was met with fierce union protests and showdowns with riot police. The Hyundai confrontation was settled peacefully in August 1998, although the number of workers to be laid off was reduced to 277, far below the announced plan. However, the Hyundai Motors layoffs established a precedent, and many chaebol began to fire large numbers of employees according to their restructuring plans as the labor movement lost public support.

The no. of financial institutions in Korea fell from 2,101 at the end of 1977 to 1,553 in November 2001 and those institutions that survived underwent significant restructuring reforms, including massive lay-offs, as a condition of capital injections and purchases of NPLs using public funds. Cho Hung Bank, for instance, released 700 of its 9,000 employees in the first half of 1998 through “honorary retirement programs” and then was forced to lay off an additional 2,949 employees in subsequent months.

As usual post-crisis, Korea's banks suffered from inadequate capitalization and poor-quality assets and thus needed recapping and disposing of their NPLs. The government stepped in with public funds and passed the “Law on Efficient Management of Non- performing Assets of Financial Institutions and Establishment of Korea Asset Management Corporation (KAMCO)” in August 1998. Pre-crisis, only loans in arrears for six months or more had been classified as NPLs, the government decided to include loans in arrears for three months in line with internationally acceptable standards.

Using this standard, the government estimated the total size of the outstanding NPLs at 118 trillion won or roughly 28% of Korea’s GDP in 1998 This was twice the amount of NPLs estimated earlier on the old asset classification standards and ended up being 30% of GDP by 2002 (160.4 trillion won). 2/3 of public funds were raised through bonds issued by KAMCO and Korea Deposit Insurance Corporation (KDIC). More than 40 trillion won was used to settle deposit insurance obligations and to provide liquidity to distressed financial institutions. The rest was for recapitalization and purchase of NPLs with better prospects for recovery.

In December 1998 the government announced its decision to sell a 51% share of the first major Korean bank ever (Korea First Bank) to a foreign consortium led by US-based Newbridge Capital.

The combination of real exchange rate depreciation and sharply higher interest rates led to a rapid rise in NPLs, especially as real estate projects went bust but widespread anecdotes about firms unable to obtain working capital, even in support of confirmed export orders from abroad were also prevalent.

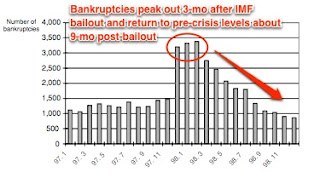

Unsurprisingly, bankruptcies soared among SMEs. The monthly average number of firms defaulting on promissory notes during 1997 was 1431, nearly a 50% increase from 966 in 1996, indicating the degree of vulnerability of the economic structure.

Income inequality dramatically widened, giving rise to suffering at the lower rungs of society (again, pretty similar to the impact we saw in Turkey - SMEs get smashed by the lack of liquidity etc). Korea’s Gini coefficient rapidly grew from 0.283 in 1997 to 0.351 in 2000.

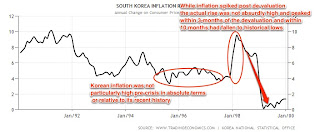

In relative terms, Korea experienced some pretty nasty inflation following the depegging of its currency - the inflation rated doubled going into early 1998. However, in absolute terms it never actually even got into double digits and by 1999 inflation was at levels below those prior to the crisis (inflation as the chart shows was pretty low before the crisis).

A negative terms-of-trade shock brought on by a rapid decline in prices for semi-conductors, steel and chemical products pressured already thin profit margins of chaebols and accelerated the downtrend of already structurally modest ROICs at these conglomerates going into 1995 (this also on a macro level aggravated Korea's current account deficit). Increasing wages at chaebol over the previous few years also did little to help.

CURRENT ACCOUNT LIBERALIZATION & DEFICIT

During the 1990s Korea posted high growth rates, savings and investment ratios; and low and declining inflation rates, and general government surplus. The only macro indicator of concern was a relatively small but growing current account deficit, which reflected a slowdown in the growth of exports from an average annual rate of 10.17% in the 1980s to 8.18% during 1990–5 and down to 4.92% in 1996. However, this was actually significant because high levels of investment and exports had supported Korea’s strong growth.A jump in the current account deficit in 1991 to $8.7bn pushed Seoul to encourage capital inflows to finance the deficit, this was done by amending the Foreign Exchange Management Act. As exports accounted for 40% of Korea’s GDP the regulatory focus on the liberalization was on the effect of capital inflows on the competitiveness of Korean exports through the appreciation of the Korean won rather than the feedthrough effect of capital inflows on financial system stability.

At end of 1996, Korea’s current account recorded a deficit of $23 billion, compared to a deficit of $8.5 billion at year-end 1995. This jump was brought on by the adoption of a strong-dollar policy adopted by the US in 1995 that caused Korean export competitiveness to suffer, particularly vis-a-vis the yen. A further headwind arose as the Chinese devalued the yuan.

In addition, FX reserves at end-1996 was equivalent to just 2.8 months of imports.

MERCHANT BANKS & FINANCIAL SECTOR LIBERALIZATION

Despite their name Korean merchant banks have little in common with institutions such as Lazards, Rothschilds, Morgan Stanley et al. The Korean merchant banks are financial institutions fairly unique to South Korea. they originally traced their history back to the 70s when a number of loan sharks for SMEs were allowed to convert to legitimate loan-broking and leasing businesses. Their primary line of business was making short-term loans especially to SMEs. (In some sense they are pretty similar to say Orix in Japan and the Chinese trust companies.)

Subsequent to the amended Foreign Exchange Management Act, in 1993, the Korean government also liberalized the financial sector loosening restrictions on asset and liability management. This led to an increase in the short-term foreign currency debts at financial institutions. Then as part of the requirements for joining the OECD in 1996, the government implemented further financial deregulation that effectively discouraged long-term foreign borrowing by business firms as it required detailed disclosure on the uses of the funds as a condition for Ministry of Finance and the Economy (MOFE) approval.

Subsequent to the amended Foreign Exchange Management Act, in 1993, the Korean government also liberalized the financial sector loosening restrictions on asset and liability management. This led to an increase in the short-term foreign currency debts at financial institutions. Then as part of the requirements for joining the OECD in 1996, the government implemented further financial deregulation that effectively discouraged long-term foreign borrowing by business firms as it required detailed disclosure on the uses of the funds as a condition for Ministry of Finance and the Economy (MOFE) approval.

On the other hand, short-term borrowing was mainly regarded as trade-related financing requiring no strict regulation.

Moerover, under the new system, merchant banks could engage in foreign-exchange transactions. 24 finance companies, which were prohibited from conducting FX transactions, transformed themselves into merchant banking corporations taking the number of merchant banks to 30 in 1996 from the original six in 1994 (sounds a little like the boom in Turkish banking in the run up to the 2001 crisis!). A number of these new merchant banks were owned by chaebol.

In the case of the six chaebols that went bankrupt in 1997 reliance on merchant banks, was very heavy. For example, the Halla group borrowed 50% of its 6·5 trillion Won debts from merchant banks.

In the case of the six chaebols that went bankrupt in 1997 reliance on merchant banks, was very heavy. For example, the Halla group borrowed 50% of its 6·5 trillion Won debts from merchant banks.

Korean banks opened 28 foreign branches which gave them greater access to foreign funds and competed with the merchant banks for business. These changes in the institutional framework contributed importantly to the rapid growth in foreign-currency borrowing by financial institutions.

The Korean banks took to procuring foreign currency funds on a short-term basis - primarily JPY out of HK - and investing it in long dated credits in Southeast Asia. Chaebol-owned merchant banks also acted as the funding channel for chaebol investments.

The total foreign debt stock of the merchant banks rose by around 60% per annum during 1994–6, from to $18.6bn (total foreign debt itself grew at a pretty pacy 33.6% per annum over the period!). Moreover, supervision of the merchant banks, unlike that of the deposit banks, was virtually non-existent as evidenced by the non-performing loan-to-capital ratio of the merchant banks coming in at 31.9% even at the end of 1996 (i.e., pre-crisis!!) versus a still punchy 12.2% in the commercial banking sector.

By end September 1997 Korea’s total external debt had risen to $120bn, up from $44bn in 1993. On conventional metrics, this didn't appear problematic: the World Bank considers countries with debt/GNP ratios under 48% as low-risk cases, but Korea’s debt/GNP ratio was only 22% in 1996, and was still around 25% on the eve of the crisis. Korea's debt service ratio (total debt service to exports of goods and services) was also well below the World Bank ‘warning’ threshold (18%) at 5·4% in 1995 and 5·8% in 1996.

However, of Korea's external debt, 58.3% was funded short-term at end-1996 up from an already high 43·7% in 1993, this compared to 20% for countries hit by the early 1980s debt crisis. Moreover, with 80% of short-term foreign debts used as funding for long-term assets. Moreover, the financial sector owned about 70% of the total foreign liabilities (i.e. $112bn), primarily concentrated among the merchant banks.

Meanwhile, the contagion from Thailand's default was working its way north: in late October 1997, Hong Kong's currency peg came under attack and triggered a sharp decline in the Hang Seng. Although the HKD peg held, foreign creditors, particularly American and Japanese banks, refused to roll over their loans to Korean financial institutions who had been aggressive off-shore borrowers through HK. This forced the Korean government to use its limited foreign currency reserves to help Korean financial institutions honor their short-term obligations.

However, of Korea's external debt, 58.3% was funded short-term at end-1996 up from an already high 43·7% in 1993, this compared to 20% for countries hit by the early 1980s debt crisis. Moreover, with 80% of short-term foreign debts used as funding for long-term assets. Moreover, the financial sector owned about 70% of the total foreign liabilities (i.e. $112bn), primarily concentrated among the merchant banks.

Meanwhile, the contagion from Thailand's default was working its way north: in late October 1997, Hong Kong's currency peg came under attack and triggered a sharp decline in the Hang Seng. Although the HKD peg held, foreign creditors, particularly American and Japanese banks, refused to roll over their loans to Korean financial institutions who had been aggressive off-shore borrowers through HK. This forced the Korean government to use its limited foreign currency reserves to help Korean financial institutions honor their short-term obligations.

When late 1997 rolled around and the situation really started getting nasty many merchant banks found their wholesale funding promptly evaporated, experienced some ridiculous currency mismatches and that their loan books were stuffed with loans to chaebol that had either gone bankrupt or sought protection from creditors. In addition, some had sizable amounts of Russian Treasury bills, as well as Thai, Indonesian, and other ASEAN bonds, which became unredeemable or had to be resold at a huge discount.

Quelle surprise, in 1998, 16 of the 24 (i.e. 2/3!!!??) merchant banks needed to be liquidated.

FX RATES, INTEREST RATES & IMF BAILOUT

Prior to the crisis, the Korean won was managed by the Bank of Korea based on a trade-weighted multi-currency basket system (effectively, this was a soft dollar peg) in which the currency was allowed to fluctuate in a daily 2.25% band.

The government’s implicit guarantee to maintain the FX rate misled business into believing FX risk did not exist. Accordingly, businesses (primarily Chaebol) and merchant banks did not consider the potential increase in the domestic cost of foreign debt.

In July 1997, having exhausted its FX reserves, Thailand's decided to float the Thai Baht and crystalized the first round of the Asian Financial Crisis. It took a few months for contagion to move north. For example, in September the Korea Development Bank, a state-run bank, was still able to issue $1.5 billion in global bonds without any difficulty. (Indeed, not only was it the largest foreign currency bond issue ever offered by a Korean bank or corporation the bank upped its offering by $500mn to $1.5bn to meet foreign demand as Southeast Asian economies stumbled.)

However, by October the Won began to depreciate rapidly.

On October 24, two days after the government announced a rescue plan for Kia, Standard and Poor’s, a U.S. credit rating firm lowered its rating on Korea’s long-term foreign-currency sovereign debt to single A-plus from double A-minus. This was the first time the nation’s credit rating had been cut, although some of Korea’s corporations and banks had been downgraded. S&P explained its action citing “the escalating cost to the government of supporting the country’s ailing corporate and financial sectors.” The government rescue of Korea First Bank (KFB) in September made the government’s official backing of the banking system’s obligations increasingly explicit.

By November 10, the won/dollar rate passed the 1,000 mark for the first time, and on November 16 Michel Camdessus, Managing Director of the IMF, secretly visited Seoul to discuss rescue loans. On November 17, another effort to soothe foreign investors’ concerns failed when the National Assembly failed to approve a package of 13 financial reform bills before the end of the regular session.

On November 19, the government announced a raft of financial stabilization measures intended to encourage stem the flow of portfolio funds out of the Korean economy. These measures included:

- Widening the acceptable band for daily foreign exchange fluctuations of the won to 10%

- Streamlining financial institution M&As

- A framework for liquidation of bad corporate debts at local and merchant banks

- Further liberalization of the bond market.

On November 21, the Korean government announced it had applied for an IMF bailout, this provoked a short term rally in Korean risk assets but then stuff reverted back into its nosedive.

On December 3, Korea and the IMF reached an agreement on a package totaling $58.4 billion that included loans worth $21 billion from the IMF, $10 billion from the World Bank, $4 billion from the ADB, and $23.4 billion from the G-7 and other countries. The nation, however, was obliged to accept some pretty strict (short-sighted/foolish?) terms and conditions imposed by the IMF. It was expected this would backstop the won and stabilize conditions.

Moreover, the $35 billion infusion was to be spread over more than two years until 2000, with instalments conditional upon progress in structural reforms and tightening of monetary and fiscal policies. Korea was only allowed to withdraw $5.6 billion immediately and $3.5 billion on December 18. I.e., there was $9.1 billion available over 15-days.

Meanwhile, short-term external debt at end-1997 exceeded available FX reserves by $54.7bn: ST external debt was $63.8 billion while usable gross foreign reserves were only $9.1 billion.

Meanwhile, short-term external debt at end-1997 exceeded available FX reserves by $54.7bn: ST external debt was $63.8 billion while usable gross foreign reserves were only $9.1 billion.

Foreign banks judged the immediate amounts available to be altogether inadequate as they wanted their cash immediately given deteriorating credit conditions. (When looked at like this it would be very unlikely that multilaterals and the developed world would have signed off on an immediate $64bn liquidity lifeline)

Thus rollovers were refused and limited foreign reserves were rapidly depleted. Foreign creditors further accelerated the withdrawal of their funds from Korea.

On December 10 Moody’s downgraded Korea’s debt again, from A3 to Baa2, semi-junk bond level. One day later, S&P also downgraded Korean debt three steps from A- to BBB-. These downgrades reflected concerns about the effective implementation of the IMF’s restructuring plan, which made it even harder for Korean banks to roll over their short term FX loans to ease a liquidity crunch.

Between December 5 to 13 FX trading ground to a halt within the first few minutes of the market opening as the Won dropped by its permitted daily limit of 10% (the won/dollar went from 1156.1 to 1719.39 over the period). Effectively, there were no sellers of US dollars for Won apart from the government, which managed to blow through $6bn in FX reserves from the IMF to defend the currency band as everyone attempted to dash for the exit.

The widened trading band was dropped on 12 December and the Won was allowed to float freely.

On December 19, at Korea’s request, Washington persuaded the IMF to quickly enter into a new round of negotiations with the Korean government for increased frontloading of bailout money and to lobby G-7 countries' banks to roll over short-term financing for the Koreans.

However, on December 21, Moody's downgraded the country's credit rating to non-investment grade, to Ba1 from Baa2, based on the outflow of funds from the markets and the resulting currency depreciation that added to the banking sector’s existing asset quality problems. Two days later, on December 23, S&P also downgraded Korea, by four steps from BBB- to B+.

While this may have been deserved, this accelerated momentum within the negative feedback loop: commercial banks were unable to issue internationally recognized letters of credit for domestic exporters and importers, since they were all rated as below investment grade, trade thus froze in the real economy. The downgrade immediately prompted a further round of credit liquidations, since many PMs were/are required to maintain investments only in investment grade securities. Moreover, the downgrade triggered various put options linked to credit ratings, enabling borrowers to call in loans immediately on the downgrade resulting in a huge credit crunch.

The now free-floating won collapsed 16.6% on December 24 to 1,964.8. Defaults within the banking system rocketed.

On December 25 the IMF and international agencies, along with the U.S. and 13 other nations, announced they would provide $10 billion immediately between then and early January to avoid a full collapse of the Korean economy, and the won/dollar exchange rate temporary exceeded 2,000 won for the first time.

An extraordinary session of the National Assembly passed a package of 13 financial reform bills on December 29. The financial reform package, which revised the laws governing the BOK and created a new financial supervisory agency, was designed to speed up the previously proposed structural renovation of the nation's financial sector. The revisions to the law governing the BOK made the central bank more independent to better enable it to control inflation and designated the head of the BOK to lead the policy-making Monetary Board.

On December 10 Moody’s downgraded Korea’s debt again, from A3 to Baa2, semi-junk bond level. One day later, S&P also downgraded Korean debt three steps from A- to BBB-. These downgrades reflected concerns about the effective implementation of the IMF’s restructuring plan, which made it even harder for Korean banks to roll over their short term FX loans to ease a liquidity crunch.

Between December 5 to 13 FX trading ground to a halt within the first few minutes of the market opening as the Won dropped by its permitted daily limit of 10% (the won/dollar went from 1156.1 to 1719.39 over the period). Effectively, there were no sellers of US dollars for Won apart from the government, which managed to blow through $6bn in FX reserves from the IMF to defend the currency band as everyone attempted to dash for the exit.

The widened trading band was dropped on 12 December and the Won was allowed to float freely.

On December 19, at Korea’s request, Washington persuaded the IMF to quickly enter into a new round of negotiations with the Korean government for increased frontloading of bailout money and to lobby G-7 countries' banks to roll over short-term financing for the Koreans.

However, on December 21, Moody's downgraded the country's credit rating to non-investment grade, to Ba1 from Baa2, based on the outflow of funds from the markets and the resulting currency depreciation that added to the banking sector’s existing asset quality problems. Two days later, on December 23, S&P also downgraded Korea, by four steps from BBB- to B+.

While this may have been deserved, this accelerated momentum within the negative feedback loop: commercial banks were unable to issue internationally recognized letters of credit for domestic exporters and importers, since they were all rated as below investment grade, trade thus froze in the real economy. The downgrade immediately prompted a further round of credit liquidations, since many PMs were/are required to maintain investments only in investment grade securities. Moreover, the downgrade triggered various put options linked to credit ratings, enabling borrowers to call in loans immediately on the downgrade resulting in a huge credit crunch.

The now free-floating won collapsed 16.6% on December 24 to 1,964.8. Defaults within the banking system rocketed.

On December 25 the IMF and international agencies, along with the U.S. and 13 other nations, announced they would provide $10 billion immediately between then and early January to avoid a full collapse of the Korean economy, and the won/dollar exchange rate temporary exceeded 2,000 won for the first time.

An extraordinary session of the National Assembly passed a package of 13 financial reform bills on December 29. The financial reform package, which revised the laws governing the BOK and created a new financial supervisory agency, was designed to speed up the previously proposed structural renovation of the nation's financial sector. The revisions to the law governing the BOK made the central bank more independent to better enable it to control inflation and designated the head of the BOK to lead the policy-making Monetary Board.

DOWNTURN & REBOUND

In early 1998 FX rates rebounded and moved around 1700 won. A Korean government delegation met 13 foreign banks in New York to reschedule short-term debt, and on January 28 they reached an agreement to roll over and extend the maturity of Korean commercial banks’ short-term debts by one to three years, with interest premiums and government payment guarantees.

On March 16, the government announced the results of additional rollover negotiations. A total of $21.8bn, representing 94.8% of the targeted short-term debt, was successfully rolled over after two and a half months of negotiations. Admittedly, these rescheduled debts came with high interest rates, ranging from 2.25% to 2.75% point above the then prevailing six-month LIBOR rate of 5.66%.

Nonetheless, after this, the market’s view on Korea improved dramatically and the won/dollar exchange rates started to stabilize, by end-1998 the FX rate had dropped back to 1,200 won (i.e. an appreciation of 37% in about a year!).

Road shows aimed at issuing global bonds to foreign investors were held from March 26 through April 3. The effort successfully issued $4 billion in bonds, $1 billion beyond the projected target of $3 billion. The successful issuance of the foreign exchange equalization fund bonds indicated that Korea could raise new money in the market.

By the end of October 1998 Korea’s external debt stood at $153.5 billion, of which short-term debt accounted for a little more than 20%, i.e. down from 58.3% at end-1996. A swing back to a current account surplus in 1998 buoyed by a general economic recovery in exports and domestic consumption later that year meant domestic banks were able to repay foreign-currency-denominated debt to the central bank and increased usable foreign exchange reserves.

By the end of October 1998 Korea’s external debt stood at $153.5 billion, of which short-term debt accounted for a little more than 20%, i.e. down from 58.3% at end-1996. A swing back to a current account surplus in 1998 buoyed by a general economic recovery in exports and domestic consumption later that year meant domestic banks were able to repay foreign-currency-denominated debt to the central bank and increased usable foreign exchange reserves.

Labor regulations relating to layoffs were introduced in February 1998 in the face of strong union resistance but at the insistence of the IMF. The new layoff law allowed companies to dismiss workers without union consent when the firm faced “emergency situations” such as an M&A. Other legislation covered bankruptcy, corporate liquidation and employment insurance, all aimed at speeding up the reform of industry structure and financial markets. Hostile mergers and acquisitions of domestic firms by foreigners were allowed as the Assembly approved a bill on the introduction of foreign capital.

Hyundai Motors announced plans for to layoff about 20 percent of its 45,000 work force in order to overcome sluggish sales and overcapacity in May 1998. This was met with fierce union protests and showdowns with riot police. The Hyundai confrontation was settled peacefully in August 1998, although the number of workers to be laid off was reduced to 277, far below the announced plan. However, the Hyundai Motors layoffs established a precedent, and many chaebol began to fire large numbers of employees according to their restructuring plans as the labor movement lost public support.

A government Chaebol reform program called for:

The chaebol were pretty successful at bringing leverage down. By end-1999, Hyundai, Samsung, LG and SK had reduced their debt-to-equity ratios below 200% at the order of the government (an average of 172.9% vs. above 300% pre-crisis). However, this was a rocky road in 1999 Daewoo, the fourth largest chaebol by assets, went bust at enormous cost. Moreover, even now it is pretty debatable that the groups are transparent, have decent governance or engage in shady shxt (e.g. SK chairman Chey Tae Won's indictment for embezzlement in 2012)... hence, the "Korea discount" the market tends to trade at.

However, IMF insistence on bank closures, capital adequacy enforcement, and tight credit conditions (via high rates) caused a shutdown in domestic Korean bank lending. Rates were raised from pre-crisis rates of 12% to 27% by the end of 1997 and up to 30% in early 1998. The objective of interest policy was to induce the investors to keep their savings in domestic currency and additionally to attract foreign investment in the hope of stabilizing the value of the Korean won. High interest rates would not only attract capital inflow but also crimp aggregate demand, which should improve the country’s trade balance.

- enhanced corporate transparency

- elimination of debt cross-guarantees

- capital structure improvement

- business concentration on core competencies and strengthened cooperation with small-and-medium-sized enterprises

- improvements in corporate governance including toughened management accountability.

- Reduction of indirect cross ownership

- prevention of anti-competitive intragroup transactions and unlawful insider trading

- prevention of the evasion of inheritance and gifts taxes

The chaebol were pretty successful at bringing leverage down. By end-1999, Hyundai, Samsung, LG and SK had reduced their debt-to-equity ratios below 200% at the order of the government (an average of 172.9% vs. above 300% pre-crisis). However, this was a rocky road in 1999 Daewoo, the fourth largest chaebol by assets, went bust at enormous cost. Moreover, even now it is pretty debatable that the groups are transparent, have decent governance or engage in shady shxt (e.g. SK chairman Chey Tae Won's indictment for embezzlement in 2012)... hence, the "Korea discount" the market tends to trade at.

However, IMF insistence on bank closures, capital adequacy enforcement, and tight credit conditions (via high rates) caused a shutdown in domestic Korean bank lending. Rates were raised from pre-crisis rates of 12% to 27% by the end of 1997 and up to 30% in early 1998. The objective of interest policy was to induce the investors to keep their savings in domestic currency and additionally to attract foreign investment in the hope of stabilizing the value of the Korean won. High interest rates would not only attract capital inflow but also crimp aggregate demand, which should improve the country’s trade balance.

The no. of financial institutions in Korea fell from 2,101 at the end of 1977 to 1,553 in November 2001 and those institutions that survived underwent significant restructuring reforms, including massive lay-offs, as a condition of capital injections and purchases of NPLs using public funds. Cho Hung Bank, for instance, released 700 of its 9,000 employees in the first half of 1998 through “honorary retirement programs” and then was forced to lay off an additional 2,949 employees in subsequent months.

As usual post-crisis, Korea's banks suffered from inadequate capitalization and poor-quality assets and thus needed recapping and disposing of their NPLs. The government stepped in with public funds and passed the “Law on Efficient Management of Non- performing Assets of Financial Institutions and Establishment of Korea Asset Management Corporation (KAMCO)” in August 1998. Pre-crisis, only loans in arrears for six months or more had been classified as NPLs, the government decided to include loans in arrears for three months in line with internationally acceptable standards.

Using this standard, the government estimated the total size of the outstanding NPLs at 118 trillion won or roughly 28% of Korea’s GDP in 1998 This was twice the amount of NPLs estimated earlier on the old asset classification standards and ended up being 30% of GDP by 2002 (160.4 trillion won). 2/3 of public funds were raised through bonds issued by KAMCO and Korea Deposit Insurance Corporation (KDIC). More than 40 trillion won was used to settle deposit insurance obligations and to provide liquidity to distressed financial institutions. The rest was for recapitalization and purchase of NPLs with better prospects for recovery.

In December 1998 the government announced its decision to sell a 51% share of the first major Korean bank ever (Korea First Bank) to a foreign consortium led by US-based Newbridge Capital.

The combination of real exchange rate depreciation and sharply higher interest rates led to a rapid rise in NPLs, especially as real estate projects went bust but widespread anecdotes about firms unable to obtain working capital, even in support of confirmed export orders from abroad were also prevalent.

Unsurprisingly, bankruptcies soared among SMEs. The monthly average number of firms defaulting on promissory notes during 1997 was 1431, nearly a 50% increase from 966 in 1996, indicating the degree of vulnerability of the economic structure.

In relative terms, Korea experienced some pretty nasty inflation following the depegging of its currency - the inflation rated doubled going into early 1998. However, in absolute terms it never actually even got into double digits and by 1999 inflation was at levels below those prior to the crisis (inflation as the chart shows was pretty low before the crisis).

The jump in bankruptcies, widening gini coefficient and spike in inflation and interest rates also lead to a consumption slump across all sectors, with the exception of heating and lighting. Expenditures on clothes and shoes marked the highest contraction (something to short then in the next crisis wherever it may be!).

Nonetheless, the rapid normalization of inflationary pressures meant interest rates came back down quite quickly. Industrial production likewise normalized/stopped shrinking about a year after the initial crisis.

Nonetheless, the rapid normalization of inflationary pressures meant interest rates came back down quite quickly. Industrial production likewise normalized/stopped shrinking about a year after the initial crisis.

Unemployment reached a record level of 8.7% in February 1999, doom-mongers at the time were expecting it to hit 10% but it it then started to drop pretty rapidly going into 1999.

Toward the end of 1998 the recovery of the rest of the economy also picked up steam. Led by the expansion of exports and domestic consumption in automobiles, semiconductors, and telecommunications, Korean industry has begun to regain much of its lost vigor. Buoyed by falling inventories and increased investment demand, FDI picked up, reaching $8.9 billion in 1998, up 27% from the previous year. Imports also picked up (mainly due to capex spending) and the country posted a trade surplus.

No comments:

Post a Comment