Totally and utterly unrelated to value investing, macroeconomics, financial crises or anything I have written about before but take six minutes out of your day to watch this segment about photographer Joel Meyerowitz. I have no idea who the guy is (being a photography philistine) but he has a wonderfully rich narrative voice and his images are fantastic...

Thursday, January 31, 2013

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Ray Dalio Davos Transcript

My friends at Santangels have a transcript of Bloomberg's roundtable with Ray Dalio at Davos. Some key quotes below,

"the most fundamental laws of economics is you can’t have debt rise faster than income. You can’t have income rise faster than productivity and the long term growth will be dependent on productivity. And we have these cycles around productivity growth because of debt cycles…

Productivity is going to be the question. There are clear benchmarks of productivity. I won’t go on, but we have a list of those things that correlate with 90 percent correlation with the outcome of the growth rate the next ten years... Productivity, because the debt cycle will no longer be the main driver...

I think in China they are in the other side of the cycle. The other side of the cycle is that debt is rising too fast relative to income and that is something that is the opposite side of the cycle and they will have to deal with it."

If you haven't read Ray Dalio's very good How The Economic Machine Works take a read here and the equally solid An In-Depth Look at Deleveragings here.

GLOBAL CAPE TALK - Mebane Faber

Brilliant talk by Mebane Faber on Global CAPE ratios and how to use them

It's common sense but well worth reflecting on

It's common sense but well worth reflecting on

Monday, January 28, 2013

Some More GMO Thoughts On Bubbles

This time though from Jeremy Grantham...

"The average of all of the bubbles we have studied... is that they go up in three and a half years, and down in three... All of them go back to the original trend, the trend that was in place before the bubble formed...

Exhibit 5 shows six bubbles from 2000. You can see how perfect they are... My favorite is the Neuer Markt in Germany, which went up twelve times in three years, and lost every penny of it in two and a half years...

the U.S. housing bubble... One reason we were so impressed with it is that there had never been a housing bubble in American history... Previously, Chicago would boom, but Florida would bust. There was always enough diversification. It took Greenspan. It took zero interest rates. It took an amazing repackaging of mortgage instruments. It took people begging other people to take equity out of their houses to buy another one down in Florida...

Stock market sectors have also bubbled unfailingly – growth stocks, value stocks, Japanese growth stocks, etc... To ignore them, I believe, is to avoid one of the best, easiest ways of making money.

At Batterymarch we invested in small cap value in 1972-73 because we had created a chart of the ebb and flow of the relative performance of small cap that went back to 1925, and we could see this big cycle of small caps. We saw the same ebbing and flowing with value...

But we didn’t keep up with small cap value, and that has been a lesson that has echoed through my life: we hit the most mammoth of home runs, and yet couldn’t beat the small cap value benchmark. (One reason was that we were picking higher quality stocks – the real survivors. From its bottom in 1974, the index was supercharged by a small army of tiny stocks selling at, say, $1⅞ a share. These stocks, which were ticketed for bankruptcy if the world stayed bad for two more quarters, instead quadrupled in... six months... Picking the right sector was, in that case, more powerful than individual stock picking. Such themes are very, very hard to beat.

Let me end by emphasizing that responding to the ebbs and flows of major cycles and saving your big bets for the outlying extremes is, in my opinion, easily the best way for a large pool of money to add value and reduce risk... The really major bubbles will wash away big slices of even the best Graham and Dodd portfolios. Ignoring them is not a good idea."

"a generalized historical observation... at least one major bank – broadly defined – would fail,”... In previous banking crises, major banks had failed, and this crisis seemed likely, to us semi-pros, to be worse than most. So we studied in broad strokes previous crises and armchaired that we should up the ante. We got lucky in an area in which we were not real experts, and we know we were lucky...

We found 28 bubbles since 1920, defined arbitrarily but reasonably as two-standard-deviation events... All but one burst all the way back to the trend that existed prior to the start of the bubble... we had expected a fairly major overrun, which is historically common... a reasonably conservative investor looking at the data would want to allow for at least a 20% overrun"

"Bubbles bursting in major asset classes are... extremely dangerous and, ironically, they really are substantially controllable by the Fed... we will all have to deal with the consequences of an excessive number of major asset bubbles breaking... the two great economic setbacks of the 20th Century – the 1929-34 Depression and the rolling depression in Japan since 1989 – were both preceded by major asset bubbles and speculation... I believe that occasional financial crises are inevitable and that they are almost always preceded by extreme speculation

GMO Feeding the Dragon & Similarity to Other Crises

I have just been reading Edward Chancellor's (of GMO) very good write up on the issues with the Chinese financial system and why it poses a systemic risk to the overall economic health of the Middle Kingdom.

"China scares us because it looks like a bubble economy. Understanding these kinds of bubbles is important because they represent a situation in which standard valuation methodologies may fail. Just as financial stocks gave a false signal of cheapness before the GFC because the credit bubble pushed their earnings well above sustainable levels and masked the risks they were taking, so some valuation models may fail in the face of the credit, real estate, and general fixed asset investment boom in China, since it has gone on long enough to warp the models’ estimation of what “normal” is."

Many of the things he and his co-author Mike Monnelly flag can be seen in the financial crisis I have looked at over the past few weeks:

FEATURE

(Identified by GMO in China)

|

ALSO SEEN IN…

|

Excessive

credit growth

(combined with an epic real estate boom)

|

Iceland, Turkey and Latvia (to be covered

later)

Also to a lesser extent in Korea but in the

corporate sector

|

Moral

hazard

(i.e., the very widespread belief that

Beijing has underwritten all bank risk)

|

Iceland; Korea and the chaebols; Turkish

banks with regards to the currency peg

|

Related-party

lending

(to local government infrastructure

projects)

|

Iceland and its holdcos, Korea and its inter-chaebol

loan guarantees, Turkey's private banks

|

Widespread

financial fraud and corruption

(from fake valuations on collateral to mis-selling of financial products) |

Iceland and the main bank shareholders

|

Contagion

risk

(posed by credit guarantee networks)

|

Iceland (love letters/collateralized

lending); Korean chaebols

|

Loan

forbearance

(aka “evergreening” of local government

loans)

|

Turkish public banks & duty losses

|

De facto financial liberalization

(which has accompanied the growth of the shadow banking system) |

Iceland, Korea, Latvia and Turkey (this

seems to be common in nearly all crises)

|

An

increase in bank off-balance-sheet exposures

(masking a rise in leverage)

|

Korean Merchant Banks

(see financial liberalization)

|

Duration

mismatches and roll-over risk

(owing to short wealth management product

maturities)

|

Iceland, Korea and Turkey (again a very

common feature)

|

Ponzi

finance

(i.e., the need for rising asset prices to

validate wealth management products and trust loans)

|

Turkish private banks with their treasury

holdings, and most of the Icelandic FX corporate loan book

|

I would also add another potential source of problems for China could be in its closed capital account and use of a currency peg. This doesn't look like a problem right now, however, pegs have frequently caused headaches/acted as preludes/catalysts for crises given the reluctance of the powers that be to abandon them when under pressure due to vested interests etc.

Iceland Financial Crisis

Ponder this:

"In 2007, just before the financial crisis, Iceland’s average income was the fifth highest in the world, 60% above US levels... Icelanders werethe happiest people in the world, according to an international study in 2006 (WorldDatabase of Happiness, 2006). They also had one of the least corrupt public administrations in the world, according to Transparency International."

18 months later things weren't so rosy

Iceland's banking sector began to grow rapidly from 2003 when state-run banks (Kaupthing, Landsbanki, and Glitnir) were privatized, the Icelandic government also decided not to tap international banks/investors to help with the transition, instead individual domestic entities gained controlling interests in the banks. The privatization of the state banks also heralded liberalization of interest rates and free flow of capital in international markets, which meant they could fully capitalize on money market funding, and open overseas branches abroad.By 2004 Iceland’s banks were competing directly with the HFF, which had been the major provider of mortgage loans. The banks did this by offering loans with lower rates, longer maturities, and higher LTVs.

In addition, the banks offered equity release mortgages/loans allowing homeowners to refinance existing mortgages and withdraw equity in their homes for consumption or investment purposes. These measures spurred an expansion in credit and caused real estate prices to soar. (Fierce competition led to a negative spreads. One of the major savings banks, for example, financed itself via long-term bonds paying 4.90% to 5.20% but at the same time lent its customers money to finance real estate at 4.15%).

This liberalization coupled with a benign international macro backdrop meant that the Icelandic grew at a brisk clip going into 2004 to 2006 fuelled by a consumption boom and a booming real estate market.

Just to egg on the consumption boom further the government also cut income tax rates for individuals one percentage point a year for three years running until 2007 and also lowered VAT (sales tax) on food products and other products. (More Range Rovers were sold in Iceland in 2006 than collectively in the other Nordic countries combined - to put that in perspective the population of Iceland is approx 300,000 or less than a tenth of Norway's, the smallest of the Scandinavian nations!)

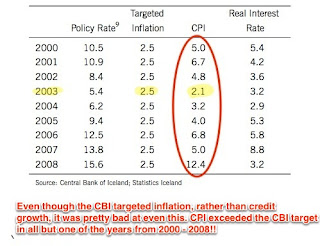

However, the economic boom led to rising inflation. The Central Bank of Iceland (CBI) began tightening monetary policy in an attempt to curtail inflationary pressures; between 2004 and 2007, it raised nominal short-term interest rates from 5% to 15%. Tighter monetary policy though was perceived by the market as akin to a CBI put option on the krona and fuelled carry-trading and demand for Krona bonds among investors, this placed further upward pressure on the value of the krona and worsened the deteriorating current account/trade deficit (something which the CBI seemed oblivious too).

The current account deficit increased every year from 2002 to 2008 and by 2007 was at a ridiculous 26% of GDP. Some of the build up can be attributed to a decision in 2003 to build the Kárahnjúkar power plant and Fjarðaál aluminium smelter, however, a substantial portion was due to capital inflows to finance carry trades/arb interest rate differentials and buy imported goods. Moreover, the savings ratio of Iceland was negative during the boom years, 2003 to 2007.

The current account deficit increased every year from 2002 to 2008 and by 2007 was at a ridiculous 26% of GDP. Some of the build up can be attributed to a decision in 2003 to build the Kárahnjúkar power plant and Fjarðaál aluminium smelter, however, a substantial portion was due to capital inflows to finance carry trades/arb interest rate differentials and buy imported goods. Moreover, the savings ratio of Iceland was negative during the boom years, 2003 to 2007.

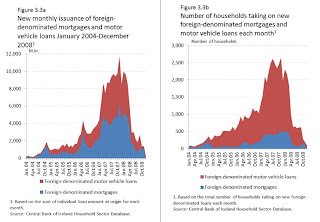

Icelandic banks and companies found it easy to issue foreign currency bonds/debt overseas or take on overseas denominated loans to exploit the lower rates and the tailwind of ISK appreciation. (In 2004, approximately 20-30% of foreign-denominated lending was directed towards firms with no offsetting foreign revenues, i.e. they were exploiting the advantageous carry and creating a growing FX mismatch between liabilities and revenues.)

By August 2005 foreign banks/issuers began to jump onto the bandwagon issuing ISK bonds to overseas investors. All this led to further ISK appreciation and made imported good cheaper… aggravating the current account etc etc. Higher demand for ISK also led to lower borrowing costs, ergo more issuance and demand, a stronger krona, easier repayment for issuers (and Icelandic consumers) and away we go again.

Moreover, as competition heated up in the housing market for mortgages lenders did not follow the CBI and start hiking their own rates (the HFF was also keen to recapture market share that the banks had been taking off it). Thus the real effective rate collapsed, which further pushed up demand for housing and inflated Icelandic residential prices. In addition, since commercial banks were willing to make loans based on a house's equity, rising equity values allowed consumers to refinance and assume higher levels of (debt-fueled) consumption.

2006 Geyser Crisis

By 2006 Iceland's current-account had swung to a deficit of 16.1% of GDP from a 1.6% surplus in 2003 and at the end of 2005, interest rates for the Icelandic banks also started rising as questions about the funding stability of short-term money markets and their impact on the Icelandic banks began to be raised, particularly regarding their ability to roll-over/refinance their large foreign currency liabilities.

Merrill, Danske Bank and the IMF all wrote critical reports about the macro situation in Iceland and in February 2006 Fitch downgraded Iceland’s outlook from stable to negative.

The krona fell sharply, the value of banks’ liabilities in foreign currencies rose, the stock market fell and business defaults rose, and the sustainability of foreign-currency debts became a public problem. The big three were forced to pay higher spreads than other European financial institutions in the same risk group in the wholesale market, which pretty much shut them out of wholesale funding: debt securities in issue in the European market shrunk to just over EUR4bn in 2006 from about EUR12bn in 2005. (A March 2006 Merrill's report noted the Icelandic banks paid 50 points above similar European Banks for funding.)

In theory, 2006 should have been the wake-up call for the banks and authorities to start sorting out the maturity and currency mismatches within the system and get a handle on the blow out in balance sheet size of the big three lenders.

Instead, the lesson the lenders and authorities took away was completely the reverse and it just accelerated the madness. With a mature domestic market the banks looked abroad to keep fuelling the balance sheet expansion (by 2006 Iceland's banks balance sheets were equivalent to over 700% of GDP and up from less than 200% in 2003!).

The krona fell sharply, the value of banks’ liabilities in foreign currencies rose, the stock market fell and business defaults rose, and the sustainability of foreign-currency debts became a public problem. The big three were forced to pay higher spreads than other European financial institutions in the same risk group in the wholesale market, which pretty much shut them out of wholesale funding: debt securities in issue in the European market shrunk to just over EUR4bn in 2006 from about EUR12bn in 2005. (A March 2006 Merrill's report noted the Icelandic banks paid 50 points above similar European Banks for funding.)

In theory, 2006 should have been the wake-up call for the banks and authorities to start sorting out the maturity and currency mismatches within the system and get a handle on the blow out in balance sheet size of the big three lenders.

Instead, the lesson the lenders and authorities took away was completely the reverse and it just accelerated the madness. With a mature domestic market the banks looked abroad to keep fuelling the balance sheet expansion (by 2006 Iceland's banks balance sheets were equivalent to over 700% of GDP and up from less than 200% in 2003!).

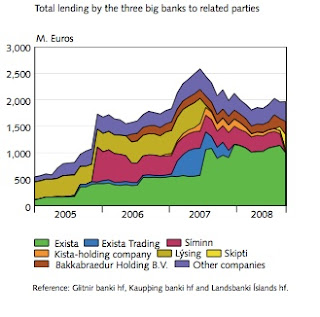

RELATED PARTY LENDING

As mentioned earlier, the Icelandic authorities eschewed cornerstone foreign investors/financial institutions coming in to take stakes in the liberalized banking sector so control of the lenders wound up in the hands of local entrepreneurs who in the best tradition of poor lending controls used the banks to bankroll their commercial empires.

(Tony Shearer, who was CEO of the British bank Singer and Friedlander when Kaupthing took it over, was shocked when he started looking into his new employer’s books. The bank had only one board member who was not Icelandic and all directors were granted loans to buy shares in the bank.)

The banks had large exposures (which really took off after 2006) to investment groups/holdco's (usually owned by their controlling shareholder) and to each other (via shareholdings)… notice any similarities with the Korean Chaebol & merchant banks or Turkish private banks?

(Tony Shearer, who was CEO of the British bank Singer and Friedlander when Kaupthing took it over, was shocked when he started looking into his new employer’s books. The bank had only one board member who was not Icelandic and all directors were granted loans to buy shares in the bank.)

The banks had large exposures (which really took off after 2006) to investment groups/holdco's (usually owned by their controlling shareholder) and to each other (via shareholdings)… notice any similarities with the Korean Chaebol & merchant banks or Turkish private banks?

As with Japan in the late 1980s, where loans were increasingly made to holding companies with the main purpose of investing in other companies the big three made loans to entities often intertwined by cross-ownership or other relations between parties in which dubious collateral was placed.

The biggest shareholder in Kaupthing Bank was Exista, with just over a 20% share in the bank. Exista was also one of the bank’s biggest debtors. Robert Tchenguiz, who owned shares in Kaupthing and Exista, had EUR2bn in loans from Kaupthing and its subs just before the lender collapsed. Notably, the bank ramped its exposure to Tchenguiz from 2007 onwards as Tchenguiz’s companies started going downhill in order for him to meet margin calls from other banks. (SEE LATER AS WELL ON GLITNIR-FL GROUP- BAUGUR)

Oh yeah, and if you didn't think they were irresponsible enough In fall 2008, while Kaupthing was in the midst of a liquidity crunch it somehow found the capital to loan key clients roughly EUR 500 million to let them sell CDS on itself!?

To finance these loans, the banks borrowed in foreign capital markets, increasing Iceland’s net external debt by 142% of GDP over the four years to end-2007.

OVERSEAS FINANCING

Oh yeah, and if you didn't think they were irresponsible enough In fall 2008, while Kaupthing was in the midst of a liquidity crunch it somehow found the capital to loan key clients roughly EUR 500 million to let them sell CDS on itself!?

To finance these loans, the banks borrowed in foreign capital markets, increasing Iceland’s net external debt by 142% of GDP over the four years to end-2007.

OVERSEAS FINANCING

Foreign deposits and short-term collateralised loans became an increasingly important source of capital for the three banks after 2006. By the end of 2007, Iceland's three largest banks relied on short-term financing for 75% of their funds, mostly through borrowing in the money markets and in the short-term interbank market.

A) European Retail Banking

With short-term money market/wholesale funding becoming expensive the banks decided to change their funding strategies. As a founding member of the European Economic Area (EEA) agreement, Icelandic banks had the right to operate within the border of other EU countries. However, until 2006 the banks never had much need to operate out of their home market.

In October 2006, Landsbanki launched Icesave in the UK, an Internet-based bank that aimed to win retail savings deposits by offering more attractive interest rates than high-street banks and was soon flooded with deposits. Millions of pounds rolled in from Cambridge University, the London Metropolitan Police Authority, and even the UK Audit Commission, as well as 300,000 retail depositors.

In October 2006, Landsbanki launched Icesave in the UK, an Internet-based bank that aimed to win retail savings deposits by offering more attractive interest rates than high-street banks and was soon flooded with deposits. Millions of pounds rolled in from Cambridge University, the London Metropolitan Police Authority, and even the UK Audit Commission, as well as 300,000 retail depositors.

At Landsbanki's insistence, Icesave was legally established as a branch rather than a subsidiary, so they were under the (more colludable) supervision of the Icelandic authorities rather than UK regulators. No one worried that, because of Iceland’s obligations as a member of the EEA (European Economic Area) deposit insurance scheme, its population of 319,000 would be responsible for compensating the depositors abroad in the event of failure.

Kaupthing also followed suit and within 18 months, the pair had amassed over £4.8 billion in UK deposits. As a group, the Icelandic banks cut their loan-to-deposit ratio to "only" 2.0x by 2007 from 3.5x in 2005. By way of comparison, have a look at the chart below on how levered the Icelandic banks were and how reliant they remained on wholesale funding for loans.

Also note most of the deleveraging of the LTD ratio came from internet deposits… who are basically yield whxres and would probably have jumped ship to anyone who was silly enough to prepare to outbid the Icelandic lenders for retail deposits. Kaupthing Edge (the bank's overseas online savings bank) was generating net inflows of ₤100–150mn/week until mid-2008.

B) Fund Management

The big three all had fund management divisions, between 2004–2008 the total AUM of the three management companies grew by over 400%, or from ISK 173 billion to 893 billion.These units however did not really begin to aggressively grow AUM until spring 2006, when European wholesale markets for Icelandic companies began to shut down due to negative publicity.

A large part of the total assets of Kaupthing’s Money Market Fund was used to invest in the parent company and undertakings related to it. During the latter half of 2006 this ratio was about 50% of the total assets of the fund and significantly higher in 2008. (At end 2007 bonds of Exista - Kaupthing's largest shareholder - alone were 20% of AUM! Talk about concentration risk!!) Note also that this was labeled a money market fund yet between 2006-08 it rarely invested in government securities and both NIBC and Norvik bank were securities of foreign banks, both banks were related parties and shared large shareholders.

Landsvaki’s Corporate Securities Fund invested in a bond issued by Björgólfur Guðmundsson (a major Landsbanki shareholder), against the will of its fund manager!

A large part of the total assets of Kaupthing’s Money Market Fund was used to invest in the parent company and undertakings related to it. During the latter half of 2006 this ratio was about 50% of the total assets of the fund and significantly higher in 2008. (At end 2007 bonds of Exista - Kaupthing's largest shareholder - alone were 20% of AUM! Talk about concentration risk!!) Note also that this was labeled a money market fund yet between 2006-08 it rarely invested in government securities and both NIBC and Norvik bank were securities of foreign banks, both banks were related parties and shared large shareholders.

Landsvaki’s Corporate Securities Fund invested in a bond issued by Björgólfur Guðmundsson (a major Landsbanki shareholder), against the will of its fund manager!

C) Glacier Bonds & CDOs

The glacier bond market boomed and by spring 2007 $6.3 billion of these bonds were outstanding - equivalent to almost 37% of Iceland's GDP - and juiced the liquidity (and liabilities) of the banks. Meanwhile, another source of regulatory/ratings arbitrage opened up: collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). Icelandic debt on paper at least had decent ratings (even if the European market was demanding higher spreads), so these could be taken into the US securitization market and bought for cheap (given the higher yield demanded by the market) and thrown into CDOs to up the rating. This way, almost EUR6bn was borrowed in the American credit market.D) Foreign Currency Loans

Households went full guns blazing into the carry trade after the Geyser crisis: JPY and CHF loans went from accounting for around 2% of overall lending to households at the beginning of 2006 to accounting for close to 20% by the time the banks fell in 2008. (Admittedly, going into late 2007 the banks wised up and started shutting down FX loans thus the tail-end of the increase in 2008 from 13% to 20% of loans was due to the weakening of the ISK.) Theoretically, FX loans were safe for banks, as the loans were hedged but there was the mismatch between hedge and loan maturity so this only provided short-term security. Moreover, while the banks may have been hedged to some degree their customers weren't and, therefore, write-downs became inevitable.

THE MELTDOWN COMETH

In 2H 2007, FL Group (now reborn as Stodir), a large Icelandic investco/holdco with a large stake in Glitnir and itself 20% owned by Baugur, posted a record loss of roughly ISK80bn. ISK60bn of this loss came in Q4 and needed to raise fresh equity; a large chunk of this was met by Baugur by selling it the real estate company Landic Property. A lot of the cash call appeared to have been bankrolled by loans from Glitnir. Glitnir’s loans to Baugur and Baugur-linked entities (e.g. FL Group etc.) went from around EUR900mn in the spring of 2007 to nearly EUR2bn a year later. At its peak related party lending comprised more than 80% of Glitnir's equity.

Meanwhile, Gnúpur, a leveraged holdco with a 3.5% stake in Kaupthing and a 10% stake in FL Group, collapsed at the end of 2007. (Leveraged cross-holdings anyone?) Gnupur's implosion triggered creditor negotiations in January 2008, a stock market sell off and considerable overseas media attention abroad. This in turn adversely affected the banks funding abilities, especially Glitnir's: it cancelled a bond issue at the beginning of the 2008 because of little investor appetite.

In February 2008, Northern Rock was nationalised in the UK after a bank-run this was followed by an outflow of deposits at Icesave (Landsbanki's UK branch/sub). Then in March 2008, Bear Stearns imploded and was sold to JPM raising global investor angst over financials and a shift to risk-off, which meant the exchange rate of the krona began to fall. Icelandic investment companies had also borrowed from overseas lenders and importantly had pledged their securities as collateral.

The decline in global equity prices and the weakening FX prompted margin calls from some foreign creditors. Some of these holdco's refinanced/met their calls by punting the cash calls back to some of the Icelandic banks in which they were large shareholders, e.g. Milestone, an investco, was facing a margin call from Morgan Stanley over loans it had received to finance the purchase of a Swedish bank (Invik,later named Moderna). Milestone eventually settled the loan but did so by getting Glitnir to take over the loan. Milestone through connected parties owned 7% of Glitnir!

Finally with the great moderation drawing to a close some of the sell-side began publishing negative reports on the Icelandic financial system and the financial press began to pick up on this.

In February 2008, Northern Rock was nationalised in the UK after a bank-run this was followed by an outflow of deposits at Icesave (Landsbanki's UK branch/sub). Then in March 2008, Bear Stearns imploded and was sold to JPM raising global investor angst over financials and a shift to risk-off, which meant the exchange rate of the krona began to fall. Icelandic investment companies had also borrowed from overseas lenders and importantly had pledged their securities as collateral.

The decline in global equity prices and the weakening FX prompted margin calls from some foreign creditors. Some of these holdco's refinanced/met their calls by punting the cash calls back to some of the Icelandic banks in which they were large shareholders, e.g. Milestone, an investco, was facing a margin call from Morgan Stanley over loans it had received to finance the purchase of a Swedish bank (Invik,later named Moderna). Milestone eventually settled the loan but did so by getting Glitnir to take over the loan. Milestone through connected parties owned 7% of Glitnir!

Finally with the great moderation drawing to a close some of the sell-side began publishing negative reports on the Icelandic financial system and the financial press began to pick up on this.

EFFORTS TO STEM OFF A BANK RUN

A) Love Letters

With the wholesale market becoming increasingly reluctant to lend to the big three they needed to find a way to either refinance existing debt or settle loans. One way they did this was to use "love letters". The Big Three would sell debt securities to smaller regional banks, which took these bonds to the CBI as collateral and borrowed against them; they then lent the fresh money back to the initiating big bank, which they could then use to redeem maturing debt.

The banks also started repeating this trick overseas by establishing Luxembourg subs to which they could sell love letters to. The subs then sold them on to the Central Bank of Luxembourg (CBL) or the ECB and upstreamed the capital back to the Icelandic parent. Between February and end April 2008 (i.e., 3 months!), the big three's subs increased their borrowing from the Central Bank of Luxembourg by €2.5 billion and from between Jan 2008 to July 2008 Icelandic collateralised loans with the ECB went from €1bn to €4.5bn! Given the inter-linkages, the big three's bank debt should not have been allowed to be used as collateral against another Icelandic bank’s borrowing.

By April, the CBL and ECB asked the Icelandic lenders and authorities informally to stop taking the pxss, but this failed and the collateralised lending kept on coming until July when the CBL stepped in and forbade love letters. Quelle surprise, in fall 2008, five counterparties defaulted on their Eurosystem loans and three of these were subsidiaries of the large Icelandic banks.

B) More Overseas Branches

In September 2007, as storm clouds began to gather over the big three Landsbanki notified the Dutch authorities that it intended to establish a branch in Holland.In May 2008, Landsbanki began to receive deposits into its Amsterdam Icesave accounts in order to access cheap retail funding to refinance its debts.

END OF THE ROAD

Given the backdrop the big three were engaged in offloading their long-term assets as fast as possible in 2008. Any ISK assets were getting clobbered and as the ISK depreciated it made it harder to meet payment of maturing short-term foreign debt. Unsurprisingly, jittery UK savers also started pulling their deposits out of the local branches. Kaupthing Edge's weekly deposit inflows of GBP100-150mn reversed to GBP50mn outflows by September 2008.

With Lehman, AIG and Merrills all going tits up in September 2008 it was pretty clear that Glitnir was not going to be able to find the capital to repay or refinance €600mn maturing in October, and so on 25 September it asked the government for a bailout. Instead, the Government, on the advice of the CBI, announced on 29 September it was taking a 75% equity stake for €600mn instead… or roughly a 2/3 haircut for the other shareholders. Not too shockingly given sentiment this intensified the bank runs and led to a sovereign downgrade (implicit support of the financial sector being taken onto the sovereign balance sheet blah, blah) and that of all the major banks.

By early October, all three banks were suffering from a severe liquidity crisis and in need of CBI emergency funding. Events then unfolded in rapid succession: an emergency law was passed on October 6th allowing the Icelandic Financial Regulatory Authority (FSA) to take over operations of illiquid banks, suspend payments in order to safeguard value and protect depositors and establish new banks to assume DOMESTIC deposit obligations and assets from failing banks. On October 7 the Icelandic Financial Supervisory Authority (FME) intervened in the operations of Glitnir and Landsbanki.

Kaupthing appeared potentially viable as a going concern and had received an 80 billion ISK loan from the government on October 6 to meet short financing. However, via its UK branch (Icesave), it had 1,200 billion ISK in liabilities (deposits) and as branch (i.e. not a subsidiary) the liability for depositor protection lay with the Icelandic state. CBI comments that the Icelandic state would not meet these obligations led to the UK using antiterrorist laws to seize the UK assets of the Icelandic banks triggering loan covenants for the group and Kaupthing was put into receivership on October 9.

Unsurprisingly, the big three had all passed "stress tests" only a few weeks earlier by the (Icelandic) FSA - there was no systemic test of the overall financial system or a proper liquidity simulation in the stress tests. The banks in theory were adequately capitalized. However, the equity was of poor quality as the collateral used to underpin the equity was often equity from related parties. In some cases, loans to third/connected parties were used to finance purchases of the bank’s own shares, i.e. effectively banks were lending money to buy shares in themselves, with those shares being the only collateral!? For example, Kaupthing Bank ultimately financed a large portion of Gnúpur’s shares in Kaupthing itself.(Clearly, the scope for abuse in manipulating one's own share price by doing this is high.) Banks would also invest their own equity alongside investments of their main borrowers completely blurring the lines between creditor and debtor. In mid-2008 weak equity amounted to just above 20 % of the capital base of Glitnir (i.e. related party shareholdings etc), stripping out intangibles and the weak equity base was about 45% of the capital base! Kaupthing, meanwhile, was happy to mark up assets it bought at inflated prices, which then contributed to its capital cushion (Olam anyone?).

How fucked was the situation?

The banks' balance sheets were 11x GDP with their FX exposure about 7.5x GDP. Meanwhile, the CBI's reserves were about 21% of GDP (i.e. 0.2x), there was 0.12x GDP (€1.5 bn) in currency swaps available with the Nordics and 0.2x in committed credit lines. So short term national liquidity was about 0.35x GDP…. versus 7.5x GDP in FX liabilities in financial sector exposure! (Yes, some of this was long duration but not 7.15x GDP's worth!)

Kaupthing appeared potentially viable as a going concern and had received an 80 billion ISK loan from the government on October 6 to meet short financing. However, via its UK branch (Icesave), it had 1,200 billion ISK in liabilities (deposits) and as branch (i.e. not a subsidiary) the liability for depositor protection lay with the Icelandic state. CBI comments that the Icelandic state would not meet these obligations led to the UK using antiterrorist laws to seize the UK assets of the Icelandic banks triggering loan covenants for the group and Kaupthing was put into receivership on October 9.

Unsurprisingly, the big three had all passed "stress tests" only a few weeks earlier by the (Icelandic) FSA - there was no systemic test of the overall financial system or a proper liquidity simulation in the stress tests. The banks in theory were adequately capitalized. However, the equity was of poor quality as the collateral used to underpin the equity was often equity from related parties. In some cases, loans to third/connected parties were used to finance purchases of the bank’s own shares, i.e. effectively banks were lending money to buy shares in themselves, with those shares being the only collateral!? For example, Kaupthing Bank ultimately financed a large portion of Gnúpur’s shares in Kaupthing itself.(Clearly, the scope for abuse in manipulating one's own share price by doing this is high.) Banks would also invest their own equity alongside investments of their main borrowers completely blurring the lines between creditor and debtor. In mid-2008 weak equity amounted to just above 20 % of the capital base of Glitnir (i.e. related party shareholdings etc), stripping out intangibles and the weak equity base was about 45% of the capital base! Kaupthing, meanwhile, was happy to mark up assets it bought at inflated prices, which then contributed to its capital cushion (Olam anyone?).

The banks' balance sheets were 11x GDP with their FX exposure about 7.5x GDP. Meanwhile, the CBI's reserves were about 21% of GDP (i.e. 0.2x), there was 0.12x GDP (€1.5 bn) in currency swaps available with the Nordics and 0.2x in committed credit lines. So short term national liquidity was about 0.35x GDP…. versus 7.5x GDP in FX liabilities in financial sector exposure! (Yes, some of this was long duration but not 7.15x GDP's worth!)

AFTER EFFECTS

FX & CAPITAL CONTROLS

The ISK promptly tanked on the nationalisation of the banks - it troughed at roughly 50% vs. pre-crisis levels against the USD. On a more practical level, the implosion of the ISK made FX loans incredibly burdensome. Icelanders were big into JPY and CHF loans for automobiles and to a lesser degree mortgages and the CHF appreciated 107% against the króna in 2008 and the JPY 145%.

Iceland has the smallest floating currency in the world (other countries the size of Iceland either do not have their own currency, e.g. Estonia, Luxembourg, Malta, or peg to another country, e.g. Barbados, Bahamas, Brunei, Latvia, Maldives etc.) and the government implemented currency controls in October 2008 on worries that any FX reserves would be totally drained due to non-residents liquidating large holdings of krona-denominated bonds and deposits (about 30% of GDP).

Foreign aid was necessary to staunch the ISK's free fall and overseas FX swap lines with overseas central banks and an IMF, Nordic bailout in November 2008 made FX available to pay for imports that the Icelandic economy needed but was unable to produce. (At one point in October Russia was about to offer a $5.4bn bailout but this freaked out the EU significantly that it prodded the IMF and Nordics into gear.)

Iceland has applied to join the EU (accession negotiations are currently underway) with a view to adopting the euro as quickly as possible. This would significantly lower FX and inflation volatility for traded goods (nearly half of Iceland’s external trade is with countries in the euro area or pegged to it), however, the actions of its banks in fxcking around with the CBL and ECB with love letters and their Dutch and UK saving bank subs/branches haven't enamoured it to the powers that be.

Iceland has applied to join the EU (accession negotiations are currently underway) with a view to adopting the euro as quickly as possible. This would significantly lower FX and inflation volatility for traded goods (nearly half of Iceland’s external trade is with countries in the euro area or pegged to it), however, the actions of its banks in fxcking around with the CBL and ECB with love letters and their Dutch and UK saving bank subs/branches haven't enamoured it to the powers that be.

In an April 2011 referendum, Icelanders voted against an agreement to reimburse the UK and Netherlands governments for the compensation payments (plus interest at 3.0-3.3% per annum) that they had made to local depositors in Icesave branches of the failed Icelandic bank, Landsbanki. This agreement would have increased Iceland’s net general government debt by less than 2% of GDP. The estimated impact was modest owing to a high expected recovery rate from the assets of the Landsbanki estate (they are expected to cover about 99% of priority claims). Unsurprisingly, Holland and the UK aren't supporting an Icelandic bid to join the EU.

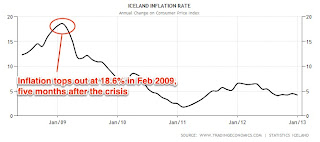

INFLATION

Inflation was relatively mild in Iceland during the boom years (mid-single digits), albeit significantly above the CBI's 2.5% target. The strong ISK also masked inflationary pressures as it made imports seem cheaper than otherwise and aggravated the current account deficit. However, once the krona and banks collapsed inflation spiked as importers were forced to pass on price rises in ISK to consumers. Moreover, given the widespread inflation indexing of mortgages (and use of loans in foreign currencies) many Icelandic households experienced a large increase in their debt levels.

Inflation though topped out 4-months after the onset of the crisis in January 2009 at 18.6% and then came rapidly down. FX stability helped bring inflation back into check, which was achieved via capital controls and, at least initially, the maintenance of interest rates at high levels. (Policy rates were high going into the crisis and from around 15% moved up to 18% before being loosened quite dramatically.)

Inflation though topped out 4-months after the onset of the crisis in January 2009 at 18.6% and then came rapidly down. FX stability helped bring inflation back into check, which was achieved via capital controls and, at least initially, the maintenance of interest rates at high levels. (Policy rates were high going into the crisis and from around 15% moved up to 18% before being loosened quite dramatically.)

As an aside, its interesting how people's expectations/forecasts often overestimate inflation in their lives (I remember one strategist - and actually normally an astute observer - flagging rising Japanese public expectations back in 2006/7 as evidence of the country shifting towards inflation.That actually never occurred.)

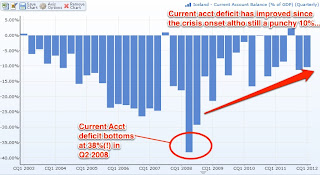

CURRENT ACCOUNT

The large current account deficits Iceland ran during the boom years were eliminated, although are still pretty large. The turnaround was/is mainly driven by the sharp import contraction. Export growth also contributed to the turnaround (aided by the currency depreciation and the new aluminum smelting capacity that was brought online), Iceland’s exports are highly concentrated in two industries: aluminium and marine/other fish products.

UNEMPLOYMENT

Unemployment rose and then topped out at 9.3% about a year and half after the crisis it has since stabilised around 5%, which is high by Icelandic standards. Average hours worked fell and wages adjusted quickly to the crisis, falling by 6¾ per cent in real terms in the year to April 2009, with the fall being much more marked in the private – than the public sector. The country also experienced very high emigration (the highest actually among Ireland, Iceland and Latvia).

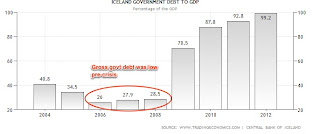

GOVT DEBT

Before the crisis, gross government debt was below 30% of GDP but started to balloon. The large fall in output (and thus taxable base) and support to the banking sector contributed to the increase in public debt (bank support boosted Icelandic public debt by about 20% of GDP). However, the government plans to achieve a primary budget surplus of at least 3% of GDP in 2013 and to increase it gradually in the following years and to restore public finances the government is implementing a fiscal consolidation programme agreed with the IMF (there is a decent amount of low hanging fruit - reversing earlier tax cuts, public sector payrises also outpaced the private sector etc.). The authorities plan to increase gradually the primary surplus beyond 2013 to bring the gross government debt-to-GDP ratio to below 60% of GDP. The government could also reduce gross debt by realizing its claims on the new banks when that becomes feasible.

FINANCIAL SECTOR RESTRUCTURING

FINANCIAL SECTOR RESTRUCTURING

Over 60% of Iceland’s external indebtedness was short-term duration, with 98% of this in the banking sector. In the run up to the collapse the CBI provided massive liquidity support to banks, which, by mid-2008, reached about 1/3 of GDP. Consequently, the CBI itself needed significant recapitalisation from the government due to bank-related losses. Losses on these loans and on bank securities held by the Treasury amounted to 13% of GDP! The CBI has since tightened rules on collateral eligible for loans.

With the collapse of the banks in October 2008, the Financial Services Authority of Iceland (FME) prepared the ground for the establishment of three new banks by carving out the old banks’ domestic operations, after their collapse, thus effectively separating domestic from foreign operations. Deposits were given first priority ahead of other claims and a blanket guarantee of all domestic deposits (by declaration, not law) prevented a run on the banks.

The Resolution Committees of the failed banks, Kaupthing and Glitnir, on behalf of their creditors, decided to recapitalise and become majority owners of the new Arion Bank and the new Íslandsbanki. The Icelandic state became the majority owner of Landsbanki, with the Resolution Committee taking a 20% stake.

The big three's assets were written down by 60%. The international businesses remained with the failed old banks for winding up. The division was complicated affair, mainly due to what the ‘fair value’ of the defaulted banks' assets were when they were transferred to the new, post-crisis banks. Restructuring of most of the financial institutions that failed in the wake of the global financial crisis was completed by the end of 2010.

All three new banks were recapitalised with strong capital ratios – in excess of 16% of all assets (in fact, most are above 20%) – and are 90% funded with deposits. Legislative reforms were implemented, including stricter rules on internal auditing responsibility and qualifications, increased responsibilities for boards and management, strict regulation of bonus pay, golden handshakes and golden parachutes.

The government also had to inject capital equivalent to 2.1% of GDP into the HFF to offset losses in its loan book. With the exception of the state-owned HFF, the Icelandic authorities imposed losses first on shareholders and subsequently on non-priority (i.e., non-deposit) unsecured creditors. This limited the direct impact on net government debt of restructuring financial institutions to around 5.9% of GDP, reflecting the cost of recapitalising the banks (3.8% of GDP) and the HFF (2.1% of GDP). This approach has strengthened market discipline, as shareholders and unsecured non-priority creditors have few grounds for expecting government bailouts to resolve financial institutions, which should reduce the incentives to pursue risky strategies and hence the probability of future financial crises.

Corporate debt restructuring proceeded slower than anticipated at first but was largely finalised in early 2012.

Finally, it is also worth reflecting on the fact that Iceland was able to return to international capital markets in June 2011 by issuing treasuries. This is remarkable as it still maintains strict capital controls and let its banks default on their foreign liabilities. It goes to show (depending on your viewpoint) that even the most hopeless cases can be rehabilitated or that markets just have incredibly short memories... or a bit of both!

Finally, it is also worth reflecting on the fact that Iceland was able to return to international capital markets in June 2011 by issuing treasuries. This is remarkable as it still maintains strict capital controls and let its banks default on their foreign liabilities. It goes to show (depending on your viewpoint) that even the most hopeless cases can be rehabilitated or that markets just have incredibly short memories... or a bit of both!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)