OK so by now the story of currency crises is beginning to run a reasonably familiar path:

- Large current account deficits (i.e. above 5% of GDP)

- Foreign capital portfolio inflows

- Domestic consumption and real estate booms fuelled by cheap and easy access to debt

- Usually some kind of currency peg or favourable carry conditions with a large degree of risk concentrated in the banking/financial system due to maturity/FX/concentration mismatches.

And Latvia was no different - the country pretty much ticks all the boxes above.

In the noughties Latvia was racking up high single digit/low double digit GDP growth rates. The country had fixed its exchange rate to the euro and allowed free capital movement. Interest rates were determined by the eurozone, which meant its real interest rate was negative and hiking rates (with no capital controls) would probably have only fuelled capital inflows in search of positive carry (a la Iceland).

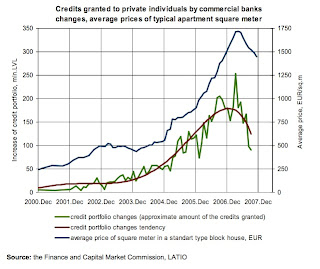

Short-term capital inflows came largely from foreign (mainly Swedish) banks, which owned about 2/3 of the banking system. This led to a large ramp up in money supply, increased inflation, rapid credit growth and a consumption and real estate boom due to easy credit conditions.

The boom in lending is best seen in the supercharged rise in total banking system assets - between Jan 2002- Jan 2008 the smallest YoY growth on a monthly basis in the Latvian banking system's total assets was 20%, most months it was growing @ c.35% and it hit 47% one month!

Expansionary bank lending stimulated mortgage growth, which grossly inflated real estate prices, both at the residential and commercial level.

The fixed exchange rate and lack of productivity growth raised production costs and priced the Baltic countries out of export markets, especially as neighboring Russia, Sweden, and Poland let their currencies depreciate. Fold in the ramp up in real estate prices and the influx of foreign capital and inflation began to run rampant, picking up aggressively going into 2008.

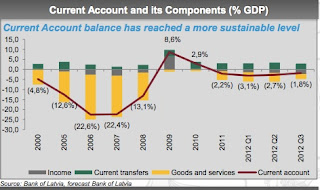

Latvia managed also to run a huge current account deficit off the back of all of this: at its peak this was around 23% of GDP. Unsurprisingly, imports were booming and saving rates were persistently negative over the period.

BTW the bulls (ahem... sell-siders) argued the current account deficit was OK because a large chunk of it was financed by long-term FDI.... actually about 8-9% was long-term FDI which still left about 15% funded by hot money!? This was mainly from foreign banks - primarily Swedish lenders who owned most of the local banking system.

"banks in current account deficit countries are generally reliant on wholesale funding. [It’s the crisis in wholesale funding that is causing the problems in American banks now.]... When a country has a fixed exchange rate that is too high (evidenced by unsustainable current account deficits) they become subject to runs on the currency... Some speculator... shorts-sells the currency and buys whatever it is fixed to... they reduce domestic money supply causing short term interest rates to rise. If they do this enough they induce a recession (ugly). This creates pressure (political and otherwise) for a deviation.

· Alternatively the central banks sterilises the money supply change. However if they continue to do this they will run out of foreign currency reserves – and the fixed exchange rate collapses anyway.

Many a fixed currency has been broken this way... a currency run results in the banks being de-funded... you need to be really careful of countries with fixed exchange rates and huge, unsustainable current account deficits.

Never much fun shorting the banks in such countries

If you had picked the collapse of the Thai Banks you might have cleverly shorted the stocks. It would not have helped much. Suppose you shorted $100 worth of a Thai bank. It collapsed down 95%... The only problem is that you have the profit in the pre-crisis exchange rate. The currency also dropped almost 90%. So you were left with about $10 profit. That is fine-and-dandy but it is not much reward for effort of picking a system that is about to collapse.

You would of course be much better just shorting the currency – or shorting the ADRs of the target stock (the ADRs being priced in a hard currency).

The real exception is that if you find a bank in a hard currency that is totally exposed to the debacle country you can make a fortune... Swedbank is my bank. It is not the only one – but is very spectacular."

THE CRISIS

Anyway, along came Lehman, everyone freaked out and realised the situation was unsustainable. The country got an EU/IMF bailout of EUR7.5bn in December 2008. The bailout forced the country to hike sales tax (i.e. fiscal consolidation in the jargon), cut public sector wages and spending and cut the budget deficit (all very Indonesia 1998!) but it allowed the country to keep its euro peg! (The IMF was actually proposing Latvia abandon the peg but there was heavy commitment to it domestically.)

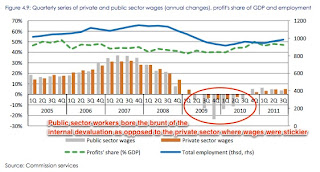

So instead of the depeg and ensuing inflation, spike in bankruptcies and banks going insolvent etc. followed by a rapid equalisation of the current account led by exports the Latvians decided to go for internal devaluation in response to the crisis (i.e. lower unit labor costs by cutting wages).

WHAT EXTERNAL DEVALUATION WOULD HAVE GOT

Given how absurd the current account deficit was, a devaluation would have been sharp if it occurred. Olivier Blanchard of the IMF estimated it would have been in the region of 50% (given how imbalanced things were this sounds reasonable, the ISK troughed at 40% of its pre-crisis levels). That would imply foreign debt doubling to around 270% of GDP and given how few payments are actually even made in lats in Latvia, it would have required a huge recap of the banking system following a wave of NPLs (primarily in euro-denominated mortgages). However, Latvia would then most likely have followed the path of most currency crises based on unsustainable pegs:

- Spike in interest rates that then start easing a quarter after the depeg

- Spike in inflation that peaks roughly 6-months after the event

- Bankruptcy and recapitalization of the banking system due to NPLs resulting from FX mismatches and higher rates

- Spike in corporate bankruptcies and mortgage defaults, usually this is quick as all/most of the leveraged entities get wiped out within a few months though their can be a 2nd spike a year later

- a mid to high single digit contraction in GDP, which then troughs roughly four quarters (i.e. a year) after the depeg (partially due to YoY effects)

- Automatic improvement in the current account due to a collapse in imports and then a rebound in exports

- Industrial production bottoming out about six/seven months from the depeg (yep, this happened but the implosion was horrific)

WHAT INTERNAL DEVALUATION GOT

The reforms sliced the number of government ministries by 30% and the no. of state agencies, closing approx. 100 schools and shutting 60% of hospitals (to 24 from 59) and slashing public sector wages. Just think about the schools and hospitals element for a moment... now I know nothing about healthcare or education in Latvia but this seems a very, very aggressive strategy.

Inflation in Q4 2009 dropped to -4.2% in Q1 2010 but had risen to 5% by mid-2011, which lowered real interest rates significantly.

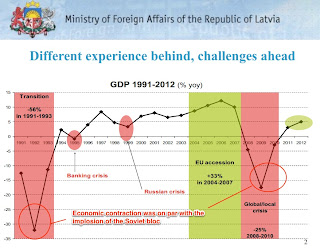

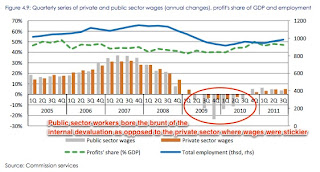

The central plank of the internal devaluation was a 26% cut in public sector wages. The misery wrought - i.e. a contraction in the ballpark experienced when the USSR collapsed - and the amount of time it took to recover vs. the other Baltics show how painful the internal devaluation route was (not to say external devaluation would have been painless either but... )

From peak to trough, Latvian GDP collapsed by 25%, which is about 2x as in Iceland and Ireland, even though in all three countries output fell back to its early 2005 level. Iceland had much higher gross and also net foreign liabilities than Latvia thus the actual debt burden shock in Iceland was much higher than what Latvia would have suffered with exchange-rate devaluation. Iceland's banking sector suffered meltdown and foreign lenders to banks suffered massive losses. Yet the crisis impact was much more benign in Iceland than Latvia (as measured by GDP contraction, unemployment etc.)

More importantly, countries that witness large, crisis-driven devaluations usually also post GDP considerably above their predevaluation level of GDP three years later. The average economy is up by 6.5% over their predevaluation level of GDP. Latvia, by contrast, was down 21.3% of GDP, three years after the crisis began.

Proponents of the peg point out that Barbados, Slovakia, and Denmark all demonstrated a peg can enforce economic discipline and facilitate structural reforms whereas a devaluation brings fast cost relief, but many countries end up in a vicious inflation-and-devaluation circle. A spirited defence of not devaluing the currency by the Gov of Barbados' central bank can be found here btw (Barbados, similar to Latvia, ignored IMF advice and went for internal devaluation of 9% of public sector wages rather than depegging back in 1991 after running large current account deficits while pegging their currency to the USD). Although the argument here seems to be more focused on the size of the economy rather than structural reforms per se.

(It's also worth flagging that a peg in itself is not needed to create a currency crisis - Iceland managed to sink the krona quite effectively by going all out on carry trading, and amassing a huge FX liabilities mismatch with overseas-denominated debts that it was incapable of paying without continued negative carry for ISK-based debtors.)

BANKING SYSTEM

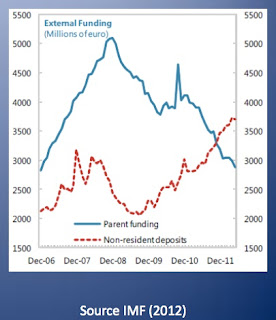

The actual cost to the Latvian govt of recapping the banking system was/is pretty small as 2/3 of the banking system is owned by Scandinavian lenders and the parents assumed the writedowns and supported their Latvian subs making the Latvian Central Bank and by extension the govt less relevant as lender-of-last-resort.

Clearly, a lot of loans were underwater post-Lehman given the property market collapsed but the decision to keep the peg also meant that NPLs rose gradually as opposed to experiencing a massive spike and killing off insolvent borrowers (see table above) and that banks didn't suddenly become insolvent overnight. (87% of Latvian loans are made in euros.)

Among domestically owned lenders only Parex Bank was nationalised - owners Valery Kargins and Viktor Krasovickis allegedly also had ties to Russian organized crime. Parex only had a 14% market share though, so the risk wasn't systemic and Latvia didn't take on an Ireland-style liability in guaranteeing/bailing out its banks.

The Swedish central bank also offered a euro/lats swap to Latvia and the ECB agreed with the Swedish central bank a Swedish krona/euro swap, thus supplying ample FX liquidity (indirectly) to maintain the peg.

According to the ECB, the loss incurred by foreign banks was about 5.7% of GDP and the loss of domestic banks about 3.6% of GDP by 2010. Punchy, but not something like Japan experienced in the late 1990s etc or Iceland for that matter. Bank support boosted the public debt/GDP ratio by about 7 percentage points of GDP by 2010. Banks have been deleveraging since November 2008 when total assets in the banking system peaked out at 23.4bn Lats and as of Nov 2012 total assets were 20bn lats (i.e., down 14.5% from the peak). However, external debt still stands at elevated levels (forecast above 130% of GDP for 2012).

CURRENT ACCOUNT SURPLUS/TRADE BALANCE

Unsurprisingly, import demand collapsed in 2009 which sliced the CA deficit in 1/2 and then pushed the country back into surplus by 2010. The CA moved back into negative territory in 2011, reflecting increased import demand on the back of an economic recovery. The deficit though is pretty modest and external financing requirements have declined from almost 500% of FX reserves in 2008. Currently, Latvia’s international reserves are about $5.5 billion, almost equaling both the $1.65 billion of lats in circulation and total bank deposits in lat of $4.2 billion, which should be enough to guarantee stability.

Manufacturing, which exports almost two-thirds of its output, performed well. The initial markets were Latvia's traditional trade partners (the Nordic and Baltic countries, Russia, and Poland, these accounted for 72% of Latvia's exports of goods in 2011) but by 2011 Latvian exporters were also expanding into other destinations and propelled most of the export growth (albeit at lower YoY rates). Admittedly, some of this is due to re-exportation and/or refining of petroleum-based products.

UNEMPLOYMENT

The internal devaluation's purpose was to bring unit labor costs down and on par with competitors and in line with productivity gains. Thus from 2000 to 2004 Latvian living standards were rising, but were rising in line with productivity and thus ULC rises were sustainable. From 2005 onwards the link was broken, and wages went ballistic. During 2008 and 2009 ULCs started to improve (partly because many unproductive workers in construction lost their jobs) and have converged with productivity gains once more.

The spike in unemployment and lower wages put pressure on private sector wages to adjust, which is more relevant for competitiveness. Quite how much these have adjusted is debatable but what is acknowledged is that it is nowhere like what the public sector felt.

Nominal wages have started rising again, however, there probably is substantial room for productivity increases given income per capita is half the EU average and it's exports are not particularly high-tech nor for that matter is the country.

Unemployment remains high at 13.5% versus pre-crisis levels (6-8%), although it has declined significantly from its peak.

CONSUMPTION

GOVERNMENT FINANCES

Latvian fiscal policy was actually pretty prudent up until the crisis (shame about the monetary policy): the country pretty much ran a balanced budget. Public debt was very low pre-crisis - low double to high single digits as a % of GDP. Even today, public debt remains around 40% of GDP and is expected to stabilize at around 45% of GDP. This more or less eliminated sovereign default concerns (also Latvia as mentioned was not on the hook for its banking system).

Latvia successfully completed its IMF/EU programme in 2011 without asking for a follow-up agreement and returned to international bond markets in 2011 (low debt to GDP helped, although its worth noting that even recidivists like Argentina were able to return to the debt markets after their default).

The crisis caused a large budget deficit, as it undermined state revenues and boosted social expenditures.

However, the 2011 fiscal deficit was reduced to below the official target of 4.5% of GDP and the government intends to bring it to 2.5% to meet the Maastricht criterion. (Also it is worth noting the insane cutbacks to the public sector also help the fiscal position as the country rebounds.)

MY THOUGHTS:

I am inclined to agree with Krugman on this one.

"Latvia’s willingness to endure extreme austerity is politically impressive, its economic data don’t support any of the claims being made about its economic lessons"

The country would have been better off pulling an Iceland if it wanted a speedy, less painful recovery. On the other hand if it is dying to get into the Euro then it has sure proved itself!